2021年12月

The Theatre & Performance collections in London’s Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) are arguably the largest and most precious in the English-speaking world. Early in 2021 news began to filter out from the museum about a consultation process and a structural reorganisation in the museum. One that was going to impact greatly on the department of Theatre & Performance with its possible dissolution as a dedicated entity and the loss of many jobs. I, in this opinion essay, look at the history of the department and the efforts that were made to fight to save it as a dedicated department and to keep the collections intact.

We all knew the pandemic has consequences for many aspects of our lives. But I had hoped that most of the cultural life in the UK would have been spared the trauma of cuts and valued as something that needed to be cushioned and protected at a very difficult time. I personally have undergone two consultation processes in my time, and I can say that they are not remotely pleasant experiences. They cause stress and damage the morale of a work force. The management of the V&A were responding to a sizable financial deficit of funds due to the COVID-19 pandemic but as with most things in life there are “different ways to skin a cat”. Cuts could have possibly been made keeping the structure of different departments intact. But as Winston Churchill once said, “never let a good crisis go to waste”, this was also possibly an opportunity to cut away “dead wood” and refocus the departments from seven material-based departments to four departments based around time and geography. Thus, arguably taking a historiological approach to the contents of the museum and less an arts-based material approach. It was also feared that Theatre & Performance would suffer a disproportionate portion of the cuts in comparison to other departments. The Theatre & Performance archives were not to close but the people behind the scenes were to dissipate into non-specialist or rather more general departments. The archives were to go to the Research Department, thus splitting up the collections. What was forgotten was the performing arts, because of its multi-material and intangible nature, need a specialist approach for materials to be linked and brought together for users.

As the president of SIBMAS (International Association of Libraries, Museums, Archives and Documentation Centers of the Performing Arts), this was a great concern and it was also my own national UK collection that was going to be impacted but it was also a blow internationally, as different countries looked to the V&A’s department as a place to study examples of best practice in saving the performing arts. There were consequences for such a reorganisation that had not really been fully considered. SIBMAS needed to highlight this situation to a wider public, the profession and the research community, thus a petition was formed and promoted. In the end our online petition got over twenty thousand signatures. The theatre industry was in effect closed at that time, so it was hard in some ways to get sympathy from the profession as they were also going through a very difficult time. But many professionals did sign the petition and I received emails of support from high profile directors, producers, and actors.

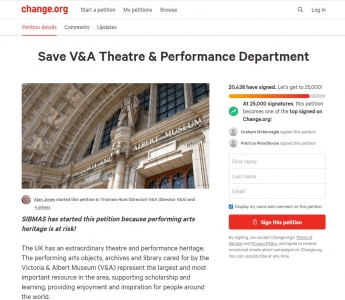

Petition of “Save V&A Theatre & Performance Department”

It was an interesting experience to lead this campaign from outside London. I had to not only deal with not only a metropolitan bias of some people in London, who were surprised there was so much passionate interest coming from north of border but also in Scotland with people not concerned by the fate of a southeast English institution. The fact the museum had a remit for the whole of the UK was not really fully understood. With the increased fracturing of the UK politically and, the rise of nationalism and English regional identities within the state, it is a surprise to some that the V&A has considerable Scottish and non-London collections. The reality was from a Scottish perspective over the years, the V&A was caring what was happened in Scotland theatre and performance wise when other institutions in Scotland were hesitant. This reluctance was caused possibly by the multimedia form that the theatre and performance collections take. A national library feels uncomfortable with objects and an art museum is not always too sure how best to manage books, costumes, and props which are not “real” objects. Consequently, the rather random arts and craft contents of the V&A mean that the theatre and performance collections somehow fit in there.

Theatre collections across the globe tend to be started by someone who are either a little mad (in a good way) or obsessive and who have a burning passion—individuals who care about theatre and performance, people who value the magic of the stage and the skills of the performers. In Germany it was an actress Clara Ziegler (1844– 1909) whose private collection which was stuffed to bursting point into her Englischer Garten villa made the base for the German Theatre Museum, now housed in the Munich Residenz. In Paris, Auguste Rondel (1858–1934), director of a bank, was fanatical about all kinds of shows in the city. He put his fortune at the service of his passion by constituting from 1890 the “Rondel collection”, the original nucleus of the department of Performing Arts of the National Library of France. In Edwardian London in the UK, Gabrielle Enthoven (1868–1950), a playwright, amateur actor and collector of ephemera of the London stage, lobbied for her collection to be taken and looked after by a major museum. The British Museum and initially the V&A were not interested. It could have gone to the Museum of London, but Enthoven argued that it needed a broader thematic and geographic reach. After the Great War her campaign finally triumphed with the V&A who took it less than enthusiastically into its care. Such was the lack of zeal of the then V&A management, she had to manage the collection unpaid herself.

Over the years the V&A became known as the place to leave theatre bequests and the collection grew. Their collecting remit developed too beyond theatre into other performing arts and popular culture in the most general sense. It also widened out of London to encompass the whole of the UK and became a national collection. Holdings now range from music hall, variety, puppetry, dance, and circus. The collection outgrew its South Kensington home and there was a call for a dedicated museum with a reading room to access the collections. The Theatre Museum was created as a distinct satellite institution in 1974 when the combined collections held by the V&A were amalgamated with those of the British Theatre Museum Association, which was founded in 1957 to collect and lobby for the formation of a separate national museum. This was supported by the Friends of the Museum of Performing Arts, another private society which pushed for the creation of a theatrical museum. They owned a lot of Ballets Russes materials which have become some of the key “jewels” of the current V&A collection. It took a few years for a dedicated building to be found, key for many was to find a home in the West End, in Theatreland. In 1987, the Theatre Museum moved into converted premises in Covent Garden. The museum found space under the London Transport Museum. In some ways the rather subterranean setting suited a theatre museum; it was dark and dramatically lit, while in other ways it was less ideal; low ceilings hampered the display of certain items like backcloths and large props. The key success was it was there at all, finally the Theatre & Performance collections had a dedicated home. In the 1990s the museum placed renewed emphasis on the acquisition of 20th century materials. In 1993 the National Video Archive of Performance filmed its first production, Richard III starring Ian McKellen. The collection included over 300 productions by 2018 and its place as a world class collection was very much evident.

In 2007 the V&A needed to make a saving of five million pounds and by some coincidence that is what it took financially to run the Theatre Museum. The collection was moved back to the V&A and much of the collection was stored in Blythe House in West Kensington. Great promises were made that the Theatre Museum would flourish as a dedicated department of the V&A. In the last 14 years the department grew and thrived and was responsible for some of the museum’s biggest blockbuster exhibitions. What was possibly forgotten by the V&A management and board of trustees, partly because none of them were around when they moved the Theatre Museum back inhouse, was the great uproar the closure caused mainly from the West End theatre people. There was a smaller hullabaloo in 2021 but in the end, the petition, letters and emails, media and social media posts had an impact. I am pleased to say that the management stepped back from their proposals and allowed a much-reduced Theatre & Performance Department to merge with the Furniture, Textiles and Fashion Department. The archives were still transferred to the Research Department, and the Theatre & Performance archivists are currently in mid-consultation about the future management of this collection. About 40% of the staff of the dedicated department have been lost and that will at some point impact on the level of work they can do but the important thing is that it is still there as an entity. I hope one day it will once again be its own dedicated department. They can currently move forward with the important work of saving, collecting, and protecting performance arts heritage. The pandemic is ongoing, but generally the department has moved on and is making the most of its new structure and working arrangements.

Prior to the pandemic there were plans to move the storage of the collections to the museum’s shiny new quarters in Stratford, V&A East Storehouse. Some viewed this project as being an expensive, vanity project and an unnecessary move but others viewed it as progress and will at some point allow greater access. 20% of the collection are books which are currently boxed up waiting for a new life in the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park building and it is hoped to have public access to these books in 2023. To box up books and not offer access for years, is not a great ways to support your users and serve the public.

If you look at any performance culture across the globe, you can take a measurement of a country’s place in the world and how they see themselves at any specific time. What will performance culture in the time of COVID-19 say about Britain? In the UK, theatre and performance form a considerable part of British cultural heritage and through time the V&A’s collection has become a vital source of information for authors, academics, designers, theatre professionals, journalists, and media producers. One of the key factors of any library or collection is the knowledge of the staff who care and develop the collections. The V&A has always had people working in the department with great specialist knowledge and performance memories, they are experts in the true meaning of the word. To reduce the number of staff, will in the end reduce the expertise resource and the importance of such a national collection.

Victoria and Albert Museum (Photo by jimmyharris, licensed under CC BY 2.0)

While on one hand theatre and performance are celebrated as key components of the culture of the nation in the UK, there is also an ambivalence about its real worth. Often this misguided viewpoint is held by some political masters and managers. Why is this so? I think this comes in part from the view that theatre and performance are sometimes seen a business rather than an art form and maybe should be at the mercy of market forces. Also, various countries and cultures tend to value different art forms more than others. Arguably, the Dutch value classical music over other art forms, the Italians value visual arts forms over performance, the French love the visual arts too with theatre and performance running a very close second. In Britain our love is the English language and literature before all other art forms. Contentious argument I know, but it is generally a truth that cultures often feel happiest when one art form expresses and represents their national psyche better than all others. Theatre and performance have yet to take first place in the national spirit, even with Shakespeare playing in a leading role.

It could be argued that the situation the department of Theatre & Performance found themselves in in 2021 highlights the need to possibly look again at how we save and promote our performance heritage and whose hands should it be safe in? The UK should have a national performing arts public access library attached to a dedicated archive and museum. We are the only major performing arts culture not to have such an institution. I hope that one day it will happen, serving all the UK, and that one day the V&A or another enlightened body will facilitate such an important dedicated organisation.

本網站內一切內容之版權均屬國際演藝評論家協會(香港分會)及原作者所有,未經本會及/或原作者書面同意,不得轉載。