2021年12月

The world of performance and that of performing arts libraries and collections are sometimes viewed as having a distant relationship but, the professional world and the collections that support them are very much interlinked. The health of one depends on the vibrancy of the other and vice versa. In this opinion essay I look at the effects of the pandemic on both and at some of the modifications it has manifested.

A cultural commentator on British television in March 2020 said we should now mark our calendar dates with B.P. for before pandemic and P.P. for post pandemic, such were the consequences of what was about to unfold. The world was going to be different; things would never be the same again akin to the coming of Christ. A rather extreme view maybe but as the pandemic stretches out into years rather than months, his words have become a little more prophetic. The pandemic has profoundly affected our working and everyday lives, through new ways of doing things and in living out our personal lives.

The rituals of a pandemic world including social distancing, wearing face-coverings, handwashing, one-way systems within the buildings framed and structured the academic year 2020/21. Along with many other UK higher education institutions, the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland (RCS) curriculum delivery was blended, incorporating both online classes and some live sessions which were recorded for virtual audiences. The RCS’s Whittaker Library responded by closing the physical space and offering a click and collect service, scanning service, digital user education and subject support via Microsoft Teams. Many performing arts collections around the globe attempted to keep services functioning in some form in the very unusual circumstance.

What the pandemic did was to create a crisis, which highlighted flaws in what we were doing—failings in society but also weakness in some of our professional practices—and uncovered some strengths too on a macro and micro level. In higher education, in the performing arts and the performing arts collections, the key strengths I believe came from the adaptability of staff to modify and change to a digital support and blended teaching and learning services. Many performing arts companies proved to be equally adaptable. Information departments and media departments were looked to to save the day and became a focus (heroes of the day) for many of the activities and changes to performance delivery.

Such societal trauma can also have positive repercussions, looking back to the last great plague of the Spanish flu in 1918. US theatre historians have pointed to the 1919 theatre strike as being a consequence of the influenza pandemic in 1918, as theatre people were dropped into great hardship. This strike led to better pay, a minimum wage, limited travel expenses and the addition of such luxuries as hot water in dressing rooms. In 1919, UK local libraries became a focus for community and health information, a role we now take for granted in a modern public library, but in the early twentieth century it was novel for a library space.

The COVID-19 pandemic may well be having a similar impact on theatre business and society but also on how we teach developing artists and manage collections. Ultimately, this situation has allowed for a fresh and different approach, with new forms of working in education and in collecting for librarians, curators, and archivists but it could be argued that it has also impacted on the creative process of some artists.

The Contemporary Performance Practice course at the RCS took the restrictions that the pandemic caused and turned them into creative and performance positives. They devised a “Manifesto for Art-Making in Times of Uncertainty” in the first week of lockdown, an outline of their key principles and tenets for working. It opens with:

We are artists!

We are creative people.

We adapt and are flexible.

We can be responsive.

We are in a hugely challenging and uncertain moment.

The students looked at themselves as burgeoning artists in a changed society and adapted made minuses into an empowerment. They looked at doing performance outside and to connect to nature, and celebrated pedagogy going online, trying to turn a negative into a positive.

Many performers looked to creating digital performances during the pandemic. Students and artists were forced to be innovative, adaptable, and forced to find new audiences and reconnect with their old audience in a different way. An arts marketing study by the Jacobson Consulting Applications (JCA) found that 43% of the digital audience had never been to a live theatre show. Key too was the idea of liveness in this digital revolution: Viewers still wanted to feel a part of a community watching a performance “live”. It could be argued that this also democratised the theatre business. Small theatre companies could be just as innovative, sometimes more so than established well-funded companies. But as of October 2021, more than 50% of UK theatre companies had dropped the digital and returned to a full programme of live inhouse productions. Digital performances empowered and developed the craft, but it did not replace it because essential to all performances is the feeling of being in a group, a community sharing an event, in a space and live at the same time. It has arguably changed the attitude of audiences, who now see performing arts companies as being multimedia organisations. Live streaming is no longer for wealthy, subsidised performing arts companies, like the Met Opera or National Theatre. It is for all. If digital performances can make a profit for a company in whatever form, they will be here to stay as people are possibly becoming more used to paying for content online.

Much Ado About Nothing under the strict COVID-19 guidelines (Photo courtesy: Royal Conservatoire of Scotland)

For theatre makers and educators, the pandemic pivot to digital has required the ongoing work of building a new knowledge base for media and platforms largely unfamiliar to them. As for performing arts archives, video collections were suddenly seen as being small goldmines to now be plundered, digitised and placed online. Many companies took to releasing archival videos of their back catalogue of shows, and a few have stepped up to produce new offerings, filmed on their stages following the COVID-19 guidelines, for virtual audiences to watch on demand too. This happened at the RCS where productions were filmed under the COVID-19 guidelines and then rebroadcast online. How successful many digitally based shows were is debatable, but at times of lockdown they were very worthwhile events, something to look forward to in a very long lockdown day. It is good news for theatre archivists, as the quality of recorded performances has increased greatly. Companies no longer view recordings of a performance as an archive document or a marketing tool, but as an asset and are often willing to fund better production values.

So much was happening in the digital sphere that it was important to try and collect this information as it could be lost. The question of how you document an industry in crisis was identified by the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas. They created the Theatre 2020 Collection project which looked for digital files from theatre professionals that could help future scholars and students understand this moment and how the theatre community responded to the pandemic. The questions asked were: How did the COVID-19 pandemic impact their careers, their organisations or theatre companies? How did their production plans adjust? They collected thousands of documents from English speaking countries across the globe. Future scholars will now have a place to go to try to understand the impacts of this global event.

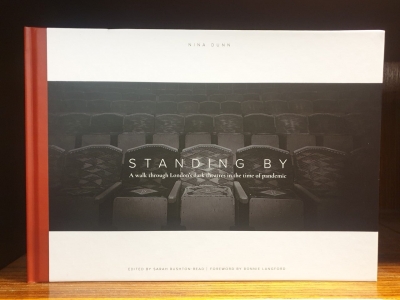

One such project that set out to capture the industry in crises was The Dark Theatres Project – A walk through iconic theatres in stasis during the pandemic, which “started as a photo essay with images captured in theatres during lockdown. These images, capturing a unique moment in time, have been published in a hardback book alongside stories from cast and crew who were in the theatres when they closed”.

Standing By published by The Dark Theatres Project (Top: Photo from the National Theatre Shop; Bottom: Photo from the website of The Dark Theatres Project)

Before closing their doors, events in performing arts collecting spanned a wide range of activities, including performances, author events, exhibitions, displays and support for student health and wellbeing. Delivering events online during lockdown allowed many library services to keep in touch with their users and reach new audiences. Theatre professionals also took to making podcasts and devising group online events. I think this trend will continue as people have become familiar with engaging via platforms like Zoom, Skype, etc. This opens great possibilities to grow events and connect with people who would not be able to attend an inhouse gathering. It could be argued that the importance of information management has increased for education and performing arts. Its relevance has been highlighted and its importance in saving performance heritage has been fuller understood.

The UK’s arts and entertainment sector has been one of the areas worst affected by the coronavirus pandemic. The decline in revenues and the number of workers furloughed was second only to the accommodation and hospitality sector. The UK government announced a support package worth £1.57 billion aimed at helping the sector recover. This money is filtering into the main spaces and companies around the UK. The West End in London is now up and running and, panto and musical tickets are being booked in Edinburgh and Leeds. Classrooms are now tentatively filling up with students and libraries are open often with restriction on the number of users. In the RCS there has been a reluctance of students to return to the physical library such has been the success of developing a digital library service. But like watching a play in the theatre, doing research in a library using physical items and space is what we all want to get back to.

Making art in an emergency is essential as it allows people to process what is happening around us. It could be argued that it is up to the performing arts and education to bring us all together again. Art, culture and education must be at the forefront of all political thinking that will lead us out of the pandemic mindset and isolationist mode. Political commentators have pointed to the similarities in citizen control and that of totalitarian countries. Any society that closes public spaces and reduces intellectual learning will falter and fade as a democracy. It is hoped that the days of closed theatre and limited student physical contact are over. The state of alarm derived from the COVID-19 pandemic was a trauma for most performing arts collections, particularly regarding the continuity of the teaching-learning activities. Although the digital transformation of collections plus teaching and learning methods is an evolutionary process that has been in development for at least 20 years, it has been slower in arts organisations. The pandemic forced a digital way of working onto the most resistant, technically Luddite members of staff, students, and professional researchers. One of the long-term consequences for collections is in space management. Architects from now on will build in structures that support social distancing, which may lead to fewer research spaces, allowing spaces to be future proof for any other viral outbreak.

The viral tsunami that COVID-19 swept into our society is now slowly washing its way out again. There was talk of the “new normal” rather than returning to what it was like before but, I think we are returning to different variants of normality. But not before altering the landscape of our professional existence, in researching, teaching and how we interact with our leisure and cultural needs.

本網站內一切內容之版權均屬國際演藝評論家協會(香港分會)及原作者所有,未經本會及/或原作者書面同意,不得轉載。