|

The Observer's Paradox?

Orderly lines, multiple displays, idiosyncratic codes, drifting dots, jumbled numbers, nonsensical sentences and high-frequency sound—they are one-of-a-kind compositional styles that audiences would have been expected to see in Ryoji Ikeda’s signature manipulation of filmic, sonic, and theatrical time/space. Over the past two decades, the artist has built a substantial career around the globe; his work has earned him recognition in the realm of digital performance, a genre incorporating computer technologies within the field of performing and media arts. On 19 November, 2016, the New Vision Festival presented Superposition, a performance that first premiered at the Centre Pompidou back in 2012, which was unquestionably one of the most anticipated titles of this year’s festival. For many media art lovers in Hong Kong, the performance was breathtaking, especially for someone seeing it live for the first time.

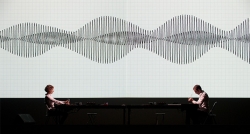

For those who are familiar with Ikeda’s works, it is not surprising to see multiple video projections and monitors. At the Sha Tin Town Hall Auditorium, the audience saw a multi-channel installation, which included three rows of screens arranged linearly across the stage. The array of screens was like a terrain of screenscape governed by the strictest formalism. In front of the floor-to-ceiling screen at the back, a long table was placed at center stage, where two keypunch devices were neatly placed at opposite ends.

The performance began with high-pitch soundwaves as expected, followed by puffs of white noise. The screens were synchronized as a series of flickering images that represented data and information, in which each image brutally punched through to the next. The visual shatter punctuated the minimal yet thrillingly complex patterns, creating a stark contrast between light and dark, between the agitation and silence. At the long table, two performers were seated neatly, as if they were keypunch operators in olden times, who then meticulously translated messages into Morse codes, yearning for skilled listeners to crack certain encrypted data. Apart from the typewriter sounds, clusters of round ball bearings occasionally rolled in all directions on the table, generating patterns of whine and strobing noise.

As for the big and small screens, much like many of Ikeda’s previous works, striking texts over a minimal background consisted of subtle kinetic dots, lines, and primary colors that ran around systematically. Some images ran too fast at times for us to tweak the details, while others ran more slowly and were less obscure. At times, the floor-to-ceiling screen was projected with live video feeds of the performers in real time. In other occasions, the video projections seemed to be prerecorded. Apart from the fact that the performance represented a big difficulty for the audience to catch up with the abundant information filled with visuals and texts, one may wonder if the actions that the performers did on stage and on the screens were coordinated and synchronized. While the projections were somewhat incomprehensible, many would give up on their strong urge to find out the logistics of the visual programming. Instead, one might believe that it was the artist’s intention to blur the borders between reality and illusion.

The audio-visual phantasmagoria orchestrated by Ikeda was centered on the complex concept of superposition, a fundamental principle of quantum mechanics. Much like many contemporary arts, Superposition seemed to be a big title, though it is questionable whether anything of substance has been reflected in the work itself. Despite the audio-visual effects of Superposition being stunning, the piece seemed to have overinflated a claim of the scientific term more to its underlying meaning. Indeed, the scientific and mathematical concepts proposed by Ikeda were visualized and digitized merely as too-slick aesthetically without remediating art with scientific reasoning or principles. While one of the paradigmatic breakthroughs in new media (art) is that it subverts the established traditions of representation, Superposition seemed to be unsuccessful in mapping its concept to a transcoding process of visualizing and sonifying data and information. Although it was apparent that Ikeda wanted to articulate the paradoxical nature of human experiences with notions of quantum mechanics by using various visual effects, the impulsive artistic depiction of data presented through a mere aesthetic strategy was yet to open a pathway to inform the audience about “the reality of nature on an atomic scale” and “the mathematical notions of quantum mechanics,” as seen in the artist statement.

It wasn’t the first time for me to watch Ikeda’s creation. Back in 2002, I watched multimedia art group Dumb Type’s Memorandum at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, in which Ikeda was one of the production members and composers of the group, and he had been since 1994. Fourteen years ago, the minimalistic use of electronic media was a cutting-edge symbolic representation of reality. As for here and now, the current bombardment of digital communication technology made prominent the question: Does the “futuristic” manipulation of visual and sound remain relevant? Indeed, Superposition looked like a dated 1990s techno-minimalist vision of the future which has never existed at the present time.

Perhaps the problem does not lie within Ikeda’s compositional style but with the increasing banalisation of (new media) art. In the context of the current speed of technologies, I couldn't help but think of Jean Baudrillard quote: “But what could art possibly mean in a world that has already become hyperrealist, cool, transparent, marketable?” The question may seem farfetched and hard to conceive, but many digital arts seem to be replicated by their self-representation of technology. Maybe the future has arrived far sooner than expected. I wonder why many so-called “digital performances” have created new artistic experiences between illusion and reality? One way or the other, it was enjoyable for me to detach myself from reality for an hour by watching and hearing Ikeda’s visual and sonic extravaganza.

本網站內一切內容之版權均屬國際演藝評論家協會(香港分會)及原作者所有,未經本會及/或原作者書面同意,不得轉載。