2015年2月

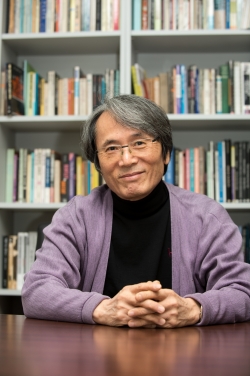

When the Minister of Culture appointed me as the Artistic Director of the National Theatre Company of Korea in February 2014, the theatre community here was divided into two groups: one welcoming, the other opposing. Quite understandably, critics and scholars welcomed and practitioners protested. Those practitioners, particularly stage directors, expressed their strong belief that this job belonged to them only. It is true that that perception is practiced much more widely around the world. Even my long-time colleague Ian Herbert from London topicalized my appointment as a very unusual case in his interview with me for The Stage.

“Some of us can remember Kenneth Tynan acting as Laurence Olivier’s right-hand man in the early days of the National Theatre, but for a critic to run a national theatre company is something of a rarity. This has recently happened in Seoul, South Korea, where Yun-Cheol Kim, whom I have known over many years as the country’s leading theatre critic, has just become director of the Korean National Theatre Company.” (December 4, 2014)

What do you think, my readers and colleagues of Hong Kong? Will you support it as my fellow critics here did, although they are turning more and more enemy-like now? One of the obvious reasons that those practitioners protested vehemently against my appointment was that I had never been a kind critic, nor had I tried hard to socialize with practitioners, for the sake of fairness in my critical judgments. This professionalism on my side was not always well appreciated by practitioners. The other big protest was based on the fact that I had no experience in producing theatre, whereas the job of an artistic director was mostly practical. This argument is very convincing, but critics nevertheless always watch closely theatre performances, both national and international, and evaluate all the practical elements of performances. You cannot say critics are ignorant of practical theatre. Besides, I have always been a prescriptive, as well as a reactive critic, like Michael Billington, whose firm belief I strongly share that “we(critics) should all have a Platonic ideal of the perfect theatre for which we should passionately fight.”[1] This code of ethic has always guided my critical profession for the past twenty-five years. I have tried my best to not bend my artistic principles and standards whenever I review performances. I have also tried my best to not fall into favouritism when reviewing shows directed or produced by my close friends. Now I feel I have to adopt this same principle, or ethic, to my new job as the Artistic Director of the NTCK. This is the only way that I can help the company grow in its artistic competence, which is my sole vision to realize.

I finally accepted the invitation from the Minister of Culture after two months of hesitation, without being apologetic. I concluded myself that I would never compromise my artistic standards even after I turned gamekeeper from poacher, that my long experience as a critic could be my strengths rather than weaknesses in moving the company one step forward artistically, that my long experience of international theatre and rich global network would be instrumental for the company to reach international standards and beyond. For the past two decades I had been the most outspoken critic of the NTCK, berating it for artistic incompetence, bureaucracy, and idleness. I felt like I had to take on the responsibility for improving the object of my critical judgments. Fortunately, the controversy over my appointment died down after a while, because the protest was more political than artistic from the very beginning.

Let me introduce the National Theatre Company of Korea and my job to you now. It was founded in 1950, just before the outbreak of the Korean War. It was set up to produce not only theatre but also Korean dance, contemporary dance, opera and Changgeuk (Korean Pansori opera), with its own choir and orchestra. The theatre company became independent in 2011 and now operates in four performance spaces, varying in size from 100 to over 500 seats. Now we produce fifteen or so new shows and play more than three hundred performances each year. I do not have any directors in residence. I invite directors that seem suited to the nature of the plays that I select. I have twenty-eight full-time staff members, a third of them technical crew, another third working for marketing, public relations, ticketing and administration. The remaining third are producers and production managers.

The Artistic Director of the NTCK takes care of both artistic and managerial affairs. I appointed a manager to take care of administration, so that I might concentrate more on artistic matters such as programming, training and education of actors, as well as promoting international exchange. I have no control over the amount of government subsidy, which is currently running at about seven million USD, but I am absolutely free in terms of artistic content. Our budget has been increasing every year, if only slightly.

On artistic policy, my priority is given to programming a repertoire that will question, analyze and define the identity of today’s Koreans. Korea has suffered long from its division between communist North and democratic South since its liberation from the Japanese rule in 1945. This ideological division has polarized even South Koreans into two political parties: nationalists sympathizing communist North and internationalists enjoying democratic South. As the result of this stark division, we elect presidents alternating between nationalists and internationalists, between leftists and rightists, between capitalists and socialists. Every five years we experience different politics, different economic policies, different cultural leadership. It is inevitable that we are suffering the loss or confusion of identity under such circumstance. I believe it is crucial for my company, as the only national theatre company in the country, to tackle this topic from diverse perspectives. In this globalized world, however, this identity can be examined by both Korean and foreign plays, traditional and modern—it depends on how we read them. I am trying to keep a balance between the Korean and international repertoires. I am moving toward a repertory system, but currently we have no permanent ensemble and cannot implement it. I have just recruited an ensemble of eighteen actors in their thirties and forties through auditions. I will increase the number every year and hope we can increasingly adopt such a system in the near future.

I will focus on tackling the identity matter, but I will do it as an internationalist. I have been an avid internationalist throughout my professional life. Working with the International Association of Theatre Critics as its executive committee member, its vice-president and president for the past twenty years, my internationalist sentiment has grown much stronger. I have promoted international exchange very hard. Although I am not in position to invite visiting companies, I invite foreign directors to direct our company two or three times in a year. Last year, for example, I invited a Romanian director Felix Alexa to direct Richard II to commemorate the 450th anniversary of Shakespeare’s birth, which was a huge success. In my fair judgment, this show was by far the best production not only for the year but for the whole history of Shakespeare in Korea. I have also invited a German playwright Nis Momme Stockmann and director Alexis Bug to write and direct The Power, which will tackle the new enslavement of modern Koreans to vicious capitalism. We will celebrate our 70th anniversary of liberation from the Japanese rule this year, and this is the way I celebrate it with a warning against our new enslavement. At the end of the year, I will invite Robert Alfoldi, a Hungarian director, to direct Shakespeare’s Winter’s Tale, that deals with reconciliation through truth, a genuine form of liberation from guilt. In 2016, I will invite a French director Jean Lambert-wild to direct Roberto Zucco by Bernard-Marie Koltes, a French classic which has a strong relevance in today’s Korea. This is not a small number, considering that we put on between fifteen and eighteen new productions in a year.

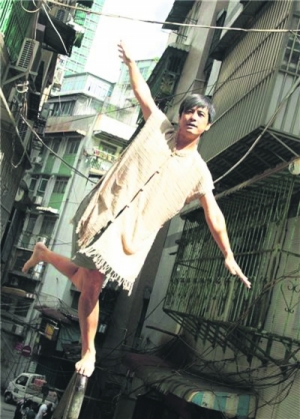

Richard II Richard II 劇照

As the Artistic Director of the NTCK, I envision the future of the company as the most important national theatre in Asia, with an internationalist perspective. I want to make it a representative Asian company that is invited frequently to international festivals around the world. For this aim, I am planning to establish a collaborating body with several prominent Asian national theatres to develop Asian repertories together. The world theatre has always been interested in Asian theatre, its dramatic literature and aesthetics, but mostly from our traditional theatre. We need to expose our modern selves and share them with the globe.

You may already have noticed my values and directions to lead the NTCK. In pursuing them, I will try to reinforce the chemical relations between theatre and story-telling. Postmodern theatre has intentionally lost those relations and thus lost a lot of theatre audiences. Theatre is basically an art form of communication between the live actors and live spectators. Language and stories are the most reliable means to achieve this. We cannot achieve this without modern and contemporary communication aesthetics. A theatre that stands in-between the convention and the revolution will serve this best. This is the theatre form that I want to realize in the nearest future. I will also aim at conception production. I agree with Irving Wardle that theatre productions with aesthetic concepts are the best and longest remembered. I think, however, this is the weakest part of Korean theatre. Our artists are not well aware of the ways to conceptualize their shows. This is one of the major benefits that I want to obtain from inviting the international directors. All of the directors I have invited so far are very competent and precise in their conceptualization of productions.

I will programme the company’s repertoire on two basic values: relevance to today’s Korean society and high artistic quality. Since the NTCK is the only national theatre in the country, and since it is 100% subsidized by the government, I want to focus our programming on productions that I feel we must pursue, that private companies cannot initiate due to financial concerns. That I feel is the raison d’etre of the only national theatre of the country.

As an expression of gratitude for your reading of my essay, I will give you a very brief introduction to contemporary Korean theatre situation, not as an artistic director, but as a critic, my long-time beloved profession. Today’s Korean theatre is extremely diverse, but its most typical form is narrative drama. Experimental or non-conventional theatre is slowly growing and becoming more and more popular among young audiences. Directors like Kim Hyun-Tak and Choi Jin-A are getting international recognition in this vein. The musical’s side, which has grown rapidly until it covers almost 80% of our theatre industry, is now in crisis. Only musicals licensed from Broadway or the West End are flourishing. There is one particular international festival in the country which demands your attention: the Seoul Performing Arts Festival. It usually takes place in October every year and invites ten or so foreign productions, mostly from Europe and Asia, along with many Korean best productions of the previous year. If you want to know sellable Korean artists, I can give you names like director-playwrights Oh Tae-Seok and Lee Yun-Taek, Pansori singer Lee Zaram, and stage director Yang Jeong-woong, whom I recommended to several international festivals, mostly in Europe. All of these people were well received there and continue to be invited due to their success with their initial productions.

I hope I have not bored you with this personal essay. I believe this case of controversy over my appointment as the Artistic Director of the national theatre here could be interesting to the critical society of Hong Kong and beyond. If I succeed, there won’t be any more argument on this topic, and I beg you to keep your fingers crossed for my success, not only for me but for your own job opportunity in the future. Thank you.

本網站內一切內容之版權均屬國際演藝評論家協會(香港分會)及原作者所有,未經本會及/或原作者書面同意,不得轉載。