2020年12月

We live in an “evolving now” where our words and actions feel more time- and date-stamped than ever before. Whatever aphorisms we carried with us into the springtime, when much of the globe went into lockdown, have no bearing on today. And whatever maxims we repeat to ourselves in the waning weeks of a year without end, will have little purchase in the months to come. The paradox of the pandemic is that for so many of us the stultifying sameness that has come to define our days is a predictor of nothing. But to hear people talk, especially now that vaccines are being distributed in wealthy global north nations, the future sounds full of guarantees. The most common refrain, “I’m looking forward to things returning to normal”, makes the future sound like it was locked in the pre-COVID past. As if the future is actually the past buried in a time capsule.

For countless performing arts festivals forced by COVID to reinvent themselves in real time, the notion that the now is a temporary breach, may very well be the only way to survive the tailspin of the present. After all, the model of programming local, national, and international productions years in advance implies a future in which the sky will not fall on our heads, and we can file into a theatre without posing an implicit biological threat to each other. Similarly, programming committees, strategic visions, and lengthy consultations with festival “stakeholders”, are all predicated on a future in which we can safely assemble. In other words, nothing about the way in which performing arts festivals normally plan is designed for this moment. (Nothing about the way in which any organization “normally” plans is designed for this moment!) No one should be taken to task for romanticizing the “normal” in the face of so much disruption, so many grievable losses.

And yet, even as we project a return to the physical scene of the festival, we (festival makers and festival goers) owe it to ourselves to ask, what are we going back to?

Do we treat 2020 like a zoonotic fluke—triaged through show cancellations, live recordings, and zoom events—or do we use this disjunction to reimagine the future? Of course, I’m wary of what I am asking here. Do curators, arts administrators, and artists even have the bandwidth to imagine differently in a year that has demanded so much from them? Is a fallow period, one without aim or output, far more necessary than reimagining what next?

For most arts workers (for most workers, paid and unpaid) fallow time is not an option. But what past and present show us is that the space of exhaustion holds its own seeds. Those who should be most depleted by war and disease are often at the frontlines of collective action and future temporalities that refuse the status quo. The historical art movements of the European avant-garde happened in the interstices of World War I, the Russian and Irish revolutions, and the global pandemic of 1918. Less than a century later, the contemporary Black Lives Matter movement was co-founded at the height of high-profile acquittals of police officers who harassed and killed Black folks in their homes, cars, and city parks.[1] Even as Black and Brown communities bore the brunt of COVID-19’s calamities people found the reserves to gather in the streets in the name of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and other Black lives taken by lethal force.[2] These events—police killings and the pandemic—should have secured a victory for nihilism. Instead, Black Lives Matter mobilized the largest global racial justice protests in living memory. In so doing, they retained the democratic right to free assembly by putting their own immune-vulnerable bodies on the line in order to demand that things be otherwise.

Racial justice protests in the name of George Floyd. Miami, Florida, USA, June 2020. (Photo by Mike Shaheen, via Wikimedia Commons)

I’m not attempting to equate distinct art and political movements, but to foreground their dual emphasis on collective embodiment and futurity in times of crisis. Both the early 20th century avant-garde and Black Lives Matter valued/value modes of public gathering that model new forms of performance and protest.[3] Moreover, both stake claims on unchartered futures through the provocation of artist manifestos, poetic visions, and public demands.

The historical avant-garde solidified the necessity of the manifesto as a space to summon the future through the performativity of writing. The experimental artists and movements that followed in subsequent waves, notably the 1960s, dispensed with the aesthetics of their predecessors, eager to make their own trails. But they retained the form, fervor, and futurism of the manifesto. In our evolving now, the Black Lives Matter movement has authored text and toolkits that address readers in the present even as they seek to reconstruct a future in which Black folks live free of fear and violence. The movement has had a powerful ripple effect across the public realm that has resulted in a range of short and longform manifestos.

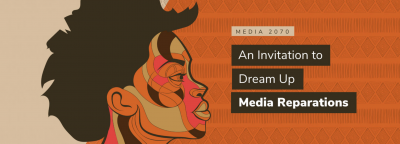

Among those texts is Media 2070: An Invitation to Dream up Media Reparations, which is core to the larger Media 2070 project.[4] The 100-page research essay is a historical account that reveals how the very origins of “media systems” in the US, namely the first newspapers in the country, relied on revenue from advertisements that trafficked enslaved Black men, women, and children as well as notices by slave owners pursuing escaped or “runaway slaves”.[5] The essay carefully works its way to the present when, in the words of the authors, “deregulation has resulted in very few Black owners of traditional media – while racist algorithms amplify the voices of white supremacists across online platforms like Facebook, Twitter and YouTube.”[6] And while Media 2070 does not call itself a manifesto, it is unmistakeably aligned with many of the genre’s characteristics. Manifestos typically arise out of the ferment of revolution, war, or periods of intense societal crisis. They make no attempt to be “neutral” or objective, but are radical in tone, and deliberately draw attention to themselves by courting antagonism and engaging in polemic. Manifestos are written works and yet, highly performative in character. They seek to mobilize people and prompt action through their words. And manifestos have an element of prophecy in that they are writing about the present but proclaiming things about the future.[7]

Cover photo of Media 2070. (Photo from the website of Media 2070)

The future orientation of Media 2070 is embedded in the project’s very title, envisioning media worlds a half century from now. It is why the history of profit and plunder they detail in the document is followed by a series of questions and demands that call for “media reparations”. The case for reparations builds on a much larger and longer conversation within African-American intellectual and civil rights circles and takes its most immediate cue from the Black Lives Matter “Reparations Now Toolkit” in which reparations are understood as both individual compensatory damages and institutional accountability and redress.[8] The Media 2070 text does not dictate the scope of media reparations, but it does invoke imagined scenarios that involve the redistribution of media resources to Black ownership and management, and the reorganization of those resources—by the print, radio, tv, and online media—to reflect the editorial vision and journalistic priorities of Black content creators and their communities. In other words, media reparations are not invested in the corporate optics of diversity and inclusion, which keep existing power structures and narratives intact. Perhaps implicitly recognizing that prophecy is paternalistic, the Media 2070 manifesto invites readers to imagine the future with them by posing a series of tantalizing questions, two of which are excerpted below:

What would it look like if we had a media system where Black people were able to create and control the distribution of our own stories and narratives?”

What would it look like if media policies ensured that Black communities had equitable ownership and control of our own local and national media outlets and over our own online media platforms? (24) [the italics are the author’s emphasis]

These questions—which fundamentally revolve about power, authorship, and audience—are also questions for the interconnected world of performing arts festivals. The “evolving now” may have upended strategic plans and advance programming, but it has also revealed that those plans and programming relied on a stagnant future. It’s why I think the question, what are we going back to?, needs to be immediately followed by another, more future-oriented one, what would it look like if…?. These questions could function as invitations from predominately white festival managers in continents such as North America, Europe, and Australia to independent Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC) curators and artists. These would not merely be flaccid consultations; in the spirit of manifestos, these invitations would shake the foundations. The permission to imagine otherwise should be as quotidian as any spreadsheet and legitimate as any blueprint in a festival office. To borrow the poetry of the Media 2070 project: “Before we can achieve the transformation [of reparations and restructuring] we need, we have to dream of a world we deserve that does not yet exist.”[9]

I want to know how choreographer Dana Michel, theatre artist Tania El Khoury, or curator Joyce Rosario would fill in the question, “what would it look like if…?”. How might these and other curators and artists of colour who have contributed so much to the life of performing arts festivals answer the question:

What could festival reparations for BIPOC artists and curators look like?[10]

Many festivals issued solidarity statements in support of Black Lives Matter over the summer months of the pandemic, but what if those same festivals had a collective ambition of festival reparations for BIPOC artists? In the “evolving now”, it is time for performing arts festivals to implicate themselves in the larger conversation about reparations and ask what form festival reparations might take within their organizations, boards, and leadership. This is not a one-size-fits-all solution. Every performing arts festival will have its uniquely local pressure points. And yet, because local, micro level issues operate within a networked global context, there is room here for performing arts festivals to crowdsource macro level ideas that can be adapted to their specific organizations and events. I want throw one such idea into the ring—redistribute and restructure—and end with an example taking place in my own backyard.

Redistribute and restructure. Because festivals are heightened, time-sensitive spaces that are invested with an aura of being “time out of time” it feels particularly apt that acts of futurity—the dream of a world that “does not yet exist”—should happen at the very scene of festivals. It is in the stages and streets of the festival that new models to redistribute power and restructure organizations could be piloted and performed. What would it look like if festivals openly tested what if scenarios that worked through new, redistributive power-sharing models? What would it look like if these what if scenarios were embedded into festival programs as curatorial interventions that took the form of performances, cabarets, critical dialogues, or public assemblies? It’s entirely possible that festivals could adopt one of these test pilots as their own organizational model with the aim to dismantle the structures that keep even the most progressive performing arts festivals in the global north predominately white in their core leadership.

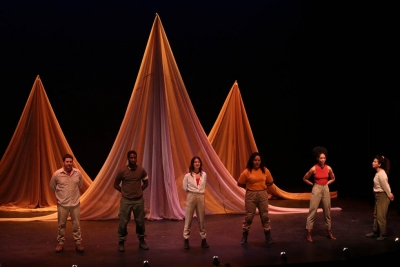

Stage photo of Black Theatre Workshop. (Photo from the website of Black Theatre Workshop)

Concrete examples can often help folks picture the other side of what if and so I will conclude here with an example from the National Arts Centre (NAC) in Ottawa, Canada. Just a few short weeks ago, the National Arts Centre English Theatre announced a new structural model for producing and programming work.[11] Starting next year, the English Theatre will shift to a collaborative structure that redistributes the power of the artistic director and the resources of the NAC. The “pilot invitation” for this collaboration was made to a “Black-mandated theatre organization to envision their mandate through a national lens.”[12] The selected company, Montreal-based Black Theatre Workshop, will operate as the Co-Curating Company in Residence and “have agency over half of English Theatre’s programming resources for the 2021–22 season.”[13] In other words, they will determine what shows are produced for the NAC stage —be it works developed from within their company’s fifty-year well of productions or shows beyond. “NAC English Theatre artistic director Jillian Keiley said under the shared curation structure, her team will work to produce shows that have been selected and developed by the Black Theatre Workshop.”[14]

For me, the example of the NAC only confirms how much I don’t want to force open the time capsule and “return to normal”. I want to be witness to what ifs. I want to feel like I am in the presence of something impossible. I want to go to the theatre, travel to a festival, and feel like I am part of a reparative body politic.

[1] Black Lives Matter was co-founded in 2013 by Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tometi, in the aftermath of the shooting death of Black teenager, Trayvon Martin. It is a movement built on evidence—the evidence of racial bias, the evidence of police misconduct, the evidence of Black death. And like the US civil rights movement before it, Black Lives Matter is a movement built on the dream of basic equality and the call for policing and criminal justice reform. It is a movement that pushes against the worn logic of the “bad apple”, the rogue cop who uses excessive force, and pushes for systemic change through the collection of large-scale data on police violence, police accountability, and police de-escalation training. It is also an abolitionist movement whose calls to defund the police, a once radical proposal, have been seriously and openly discussed in cities from San Francisco to Minneapolis. Black Lives Matter is the collective refusal to bend to a reality in which the choking deaths of men in broad day light and the shooting deaths of a child at play in the park (Tamir Rice) or a woman asleep in her own home (Breonna Taylor) are somehow exceptional rather than endemic to how Black bodies are policed. In the words of filmmaker Ava DuVernay, “the system isn’t broken. The system was built this way.”

[2] See the hashtag project, #saytheirnames, which archives and publicly lists the names of Black people in the US who perished at the hands of the police.

[3] The examples are varied and far too numerous to name here, but within the experimental avant-garde, the Cabaret Voltaire, the Zurich art nightclub, that drew together artists displaced by World War 1, stands out as a site of experimentation in both form and stage/audience relationships. Within Black Lives Matter, it has been well documented that the movement has coalesced new and existing modes of performative protest. See Nicholas Mirzeoff’s book, The Appearance of Black Lives Matter (NAME 2017), which testifies to the singularity of mass choreography actions such as, “Hands Up, Don’t Shoot”, and “I Can’t Breathe”. These choreographic and rhetorical practices amplify (through massed bodies and voices) the stolen futures of the dead.

[4] In the words of the Media 2070 Project: “we seek to work in a Black-led coalition that is abundant with journalists, technologists, artists, activists, policymakers, media-makers, organizers and scholars, including those who have long fought for reparations.” See “About Media 2070.” https://mediareparations.org/about/

[5] Media 2070 define “media systems” in specific terms worth repeating here:

We primarily use this term in reference to corporate-owned print, radio, television and online outlets that provide the majority of mass communication and information to the U.S. public. This white-controlled system is defined by policies and narrative practices that uphold a white-racial hierarchy — even amid efforts to diversify newsrooms and on-screen representation. This system also encompasses government policies that ensure white-owned media companies maintain ownership and control of the media infrastructure.

See “Definition and Terms.” https://mediareparations.org/about/#definitions-and-terms.

[6] See Media 2070 essay/manifesto, chapter eighteen (page 83-88), “Black Activists Confront Online Gatekeepers.”

[7] This swift definitional overview is indebted to Martin Puchner’s Poetry of the Revolution: Marx, manifestos, and the Avant-Gardes. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005.

[8] The Media 2070 essay (page 93) quotes the BLM Reparations Toolkit directly: “As the Movement for Black Lives policy toolkit on reparations states, realizing justice requires a ‘systematic accounting, acknowledgement, and repair of past and ongoing harms, monetary compensation to individuals and institutions led by and accountable to Black communities, and an end to present day policies and practices that perpetuate harms rooted in a history of anti-Black racism, along with a guarantee that they will not be repeated.’”

[9] Media 2070: Media 2070: An Invitation to Dream up Media Reparations (page 10). In many ways, the poetry of this manifesto is aligned with the aesthetic spirit and political priorities of Afrofuturism.

[10] I am adapting this question directly from the Media 2070 manifesto in which, on page 96 of the essay they ask: “What could media reparations for Black people look like?”

[11] The National Arts Centre in Ottawa, Canada, is a coalition of theatre, dance, and music streams that, in addition to English Theatre, includes French Theatre and Indigenous Theatre.

[12] See the NAC press release, “Black Theatre Workshop named inaugural Co-Curating Company for NAC English Theatre.” https://nac-cna.ca/en/stories/story/english-theatre-co-curator-BTW

[13] Ibid.

[14] “NAC Partners with Black Theatre Workshop.” CBC Ottawa. Canadian Press, December 9, 2020. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/ottawa/nac-black-theatre-workshop-1.5834460

本網站內一切內容之版權均屬國際演藝評論家協會(香港分會)及原作者所有,未經本會及/或原作者書面同意,不得轉載。