2018年10月

As a federated nation, the events and organisations that comprise Australia’s arts and culture are spread out over the vast 7.6 million km2 of its six states and two territories, each location having a distinct character. The national gallery and museum can be found in the national capital, Canberra. The iconic Sydney Opera House is located in Sydney, New South Wales. Melbourne, in Victoria, is the heart of the nation’s performing arts, boasting the Victorian Arts Centre and a unique collection of heritage theatres from the nineteenth century. Hobart, in Tasmania, has the world-famous Museum of Old and New Art (MONA); Brisbane, in Queensland, the equally impressive and now-ten-years-old Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA); while the tiny outback town of Tamworth is the centre of Australia’s country music scene.

Adelaide is one of the smaller state capitals, with just over one million inhabitants. Yet it is home to no less ten festivals, giving South Australia the status of the nation’s “festival state”. Founded in 1960, the Adelaide Festival is the oldest and largest event-based performing arts festival in Australia. In 2017 it sold 650,000+ tickets (for those not good at math, that’s more than half the city’s population). For one month, in early autumn—“Mad March”—Adelaide becomes the buzzing cultural hub of the country, its beautiful parks and boulevards packed with locals and interstate visitors keen to see the latest productions and exhibitions from overseas.

While the Adelaide Festival is a significant time in the artistic life of the nation, it traditionally looks to Europe and the United States for its programme inclusions. Yet as a glance at Google Maps shows, Australia is part of the Asia-Pacific region, closer to Lombok than London, New Guinea than New York.

Twelve years ago, therefore, a very different festival started up in Adelaide, and has grown exponentially to become an important contributor, and sometimes challenger, to Australians’ understanding of culture: the OzAsia Festival. Its website gives a sense of the newer organisation’s aims and scope:

OzAsia Festival is Australia’s leading international arts festival engaging with Asia. Held over 18 days [in] spring, the… [it] presents the very best in contemporary dance, theatre, music, visual art, film, literature, food, family events, workshops, talks and more from across Asia today. The expansive and innovative program attracts critical acclaim and praise annually, and is expected to attract 190,000 people over the duration of the festival. “With our most expansive and diverse program to date, OzAsia Festival continues to lead the way as Australia’s major arts festival engaging with Asia. This year’s program showcases the breadth of boundary pushing contemporary arts from across Asia as well as explores Australia-Asia collaboration. There is something for everyone in this year’s program across both free and ticketed events.” Joseph Mitchell, Artistic Director.

The Moon Lantern Parade, OzAsia Festival 2018. Attendance: 35,000 people.

Held in late October, 2018 has seen one of OzAsia’s largest ever offerings, featuring a record of 60 performing arts events over 250 scheduled performances, including 5 world premieres and 20 Australian premieres. These were accompanied by 55 talk events, 66 workshops, and 8 major visual arts exhibitions. Over 800 artists participated, from 19 countries, including Cambodia, China, Indonesia, East Timor, Japan, Malaysia, South Korea, Thailand, the Philippines, Taiwan and Hong Kong. Audience participation figures are also rising rapidly, meaning that not only is OzAsia a significant addition to Adelaide’s festival calendar, but there is also considerable popular interest in the cultural diversity it showcases.

Looking at the 2018 programme reveals an impressive array of dance, drama, visual extravaganza and cross-art form experiment: dancing grandmothers from Korea (choreographer Eun-Me Ahn), intricately scripted comedy from China (Stan Lai and Performance Workshop), immersive art installation from Japan (visual artist Ryoni Ikeda), documentary theatre from Malaysia (an adaptation of the “Baling Talks” transcripts), and hip hop from Australia (Filipino-Aboriginal rapper and composer, DOBBY). These are but a small sample of a Festival whose depth, range and brilliance opens up a new front of engagement with the region Australia is increasingly a part of.

Before looking at two productions in greater detail, it is worth considering what the Festival represents from a broader point of view. Like the adjective “European”, a soapy catch-all for countries of very different histories and outlooks, the term “Asian” says little about the cultures it labels save their geographical proximity. The broadcasting of this fact alone is perhaps the OzAsia Festival’s most significant task—to invite Australians used to thinking of the nations closest to them as a homogenous geo-political blob into a more nuanced conversation that recognises and respects their diversity and otherness.

Artistic exchange is a great place to start, not only because it represents the face of modern diplomacy (aka ‘soft power’) but also because it is a lot of fun. The OzAsia Festival is instructive because it is enjoyable, and the vibrancy and colour of its events is a message in itself. There is a sense of freedom and openness to the Festival which hopefully it will never lose. Expectations are high, but loosely defined. Audiences look to it with a desire to be surprised as well as impressed.

SUTRA

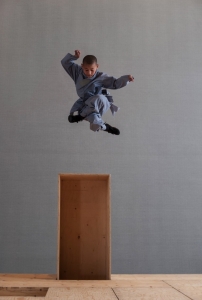

Sutra, OzAsia Festival 2018.

Sutra, a collaboration between choreographer, Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui, and a troupe of Shaolin monks, is a revival of an award-winning work in its tenth anniversary year. Cherkaoui, currently an Associate Artist at Sadler’s Wells Theatre in London, performs in a piece informed by a variety of cultural cross-currents. The music is by Polish composer Szymon Brzóska, the design of two dozen, eight-foot-tall, open-sided wooden boxes (see photograph above) by British installation artist Antony Gormley, and the production includes the extraordinary talents of nine Shaolin monks.

Over the course of an hour, Cherkaoui and the monks weave a web of hypnotic muscularity and resonant image, flinging their boxes from one side of the theatre to the other as if they were as light as paper, creating, by turns, walls, boats, ramparts, isolated altars, and a conjoined landmass. The choreography works by juxtaposition, Cherkaoui’s diffident but disciplined ambling contrasting with the fighting moves of the monks, who leap and thrust in a memorable display of martial brilliance.

At the front of the stage is a child’s game—a collection of bricks—an isomorph of the set design, manipulated by a Shaolin monk child, who is later sucked into the adult action, sometimes as Cherkaoui’s small companion, sometimes as a trainee member of the monk troupe.

It is hard to put your finger of “the theme” of Sutra, though it pulses with meaning at every point. At some moments, Cherkaoui seems Chaplin-esque in his bemused tripping-ness. At others, he is the universal refugee, the eternal sans papier, in flight from one warzone to the next, always a hair’s breath away from loss and destruction. Or that’s what came in to my mind as I watched this enthralling show. Perhaps Sutra is the dance equivalent of a dream-catcher, scooping up audience thoughts and feelings and amplifying them through the lens of its corporeal agility and imagination.

Sutra, OzAsia Festival 2018.

Here is the Message you Asked for…. Don’t Tell Anyone Else ;-)

It isn’t often that a piece of theatre which defies every genre category whatsoever appears. Typically, theatre productions that are celebrated as fresh and innovative are a hybrid or a mutation of existing forms and styles: a synthesis more than a genesis.

There are reasons for this. Theatre artists have to deal with immediate, and immediately expressed, audience expectations. A painting can hang on a gallery wall for 100 years before being recognised as a masterpiece, and a book can sit on a library shelf for even longer before being read. No live performance outlasts its time-bound presentation. Even when the written text survives, we have a fragment of the event, not the event itself.

A theatre production that does not meet some idea of what spectators think it ought to be, is one whose extinction is assured. Not for nothing do we talk about a show dying on stage. Within minutes, audiences will have decided whether it “works” or not. To keep them in suspense, to keep them looking and thinking and engaged for 90 minutes and yet not be able to pass judgment, is a challenge that would make most artists quail.

It is one that Here is the Message…, takes on directly. The programme synopsis from director Sun Xiaoxing, a leading Beijing fringe theatre creator, is the closest thing to a linear explanation of the show’s action:

A group of millennial girls sit in a fishbowl dormitory, using their phones and doing whatever takes their fancy. Surreal and self-obsessed, the girls simultaneously exist in the real world and a virtual fantasy: a hypnotic mix of screens, junk food, cosplay, living streaming, stuffed cartoon characters and live post-rock music. The audience is both observer and participant, encouraged to download a social app to exchange texts with the girls during the performance. Here is the Message… is a raw portrait of digital disconnection and the increasing cyber reality encroaching on our lives today.

Superficially, Here is the Message… resembles what Western theatre-knowledgeable people would call “a happening”. The script—if indeed there is a script—is low-key, almost throw-away. It is also entirely in Mandarin, which makes the dialogue an acoustic rather than a semantic experience for non-Chinese audiences. The seven performers—two of whom perform musical instruments—spend most of the time in gauze-covered bunk beds onto which are projected a series of images that are, by turns, surreal, mundane, disturbing and unfathomable (the one that has lodged in my mind is a food advertisement in which a dinner fork seems to stab deeply into an actor’s back).

Here is the Message…, OzAsia Festival 2018.

From time to time, the girls migrate to each other’s cubicles, and talk face to face, though computer keyboards are never far away from their fingertips. And this is true of the audience also. For Here is the Message… is two shows. The first, is the one seen on stage. The second, is in a conversation held by the audience during the show on WeChat, a smartphone app allowing a group discussion, which spectators are encouraged to download before the beginning.

This is something I did reluctantly. Digital communication interventions in live theatre have always struck me as clumsy at best, faddish at worst. The WeChat conversation in Here is the Message… did not change my view of phones in shows, but it did restore my faith in humanity. About half way through, two things became evident: First, that the overwhelmingly English-speaking audience had no idea what was going on; second, that they were nevertheless determined to make sense of it right to the end—which in this case, involved four performers ascending to the back of the auditorium, and ripping up a collection of stuffed toy animals, and throwing their dismembered parts at the heads of spectators.

Weird, definitely. Bemusing, perhaps. If Sutra brings Asia closer to non-Asian audiences by blending “Asian” performance forms with Western expectations, Here is the Message… does the opposite, taking Western technology and bending it to the sensibility of Chinese youth. The result is pure “otherness” on stage, an “otherness” Australians would be wise to ponder, given that the world does not look, sound or feel the same in Shanghai as it does in Sydney.

Here is the Message…, OzAsia Festival 2018.

The OzAsia Festival for 2019 will no doubt contain a new array of talents, activities and art forms. No doubt too, it will continue to grow in both size and scope. It has already achieved a momentum in 12 years that the Adelaide Festival took 30 years to reach. This reflects a new social reality: that Australia is surrounded by a diversity of Asian artists who have been only rarely seen on our stages. Their appearance now marks more than simply a new market presence. It marks the exciting development of a new cultural relationship with the region.

本網站內一切內容之版權均屬國際演藝評論家協會(香港分會)及原作者所有,未經本會及/或原作者書面同意,不得轉載。