2018年2月

This article is about the history of theatre in Iraq and also in Kurdistan. Here by Kurdistan[1] I mean South Kurdistan, which has been recognised as an autonomous region in the north of Iraq.

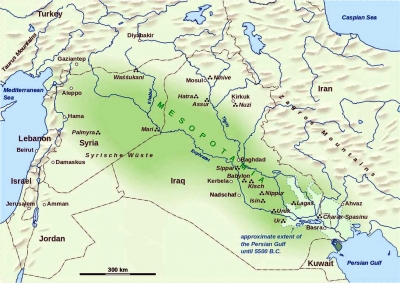

Mesopotamia – the land between two rivers (Online Image)

The first part will cover the ancient theatre in Mesopotamia, a historical region in West Asia located in the heart of the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in modern days roughly corresponding to most territories of Iraq, plus Kuwait, the eastern parts of Syria, southeastern Turkey, and regions along the Turkish–Syrian and Iran–Iraq borders.

Broadly speaking, the (Kurdish and Arabic) theatres share a common history which goes back to the late 19th century. My article shows that the two theatres have many things in common. The two major races, Kurds and Arabs, and many other ethnic minorities have been living together despite their differences in language, culture, and religion. They have many common traditions as well, such as the development of theatre.

The second part of this article will cover the recent history of theatre in Iraq. This part can be divided into three periods: the first is theatre in Iraq and Kurdistan after the Revolution of July 14, 1958; the second is Kurdish theatre from 1991 until now; and the third is Iraqi theatre from 2003 (after the fall of the Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein) until present. Here, I have to separate Kurdish theatre from Iraqi Arab theatre as they have developed differently.

History of Ancient Theatre in Iraq and Kurdistan

In order to understand the history of theatre in Iraq, one has to first describe the background for theatre in the countries that make up the so-called Arab world today. How far one has to go back depends on how one reads its history. A conventional perception among theatre practitioners and historians, both Arab and Western, is that the word ‘theatre’, as it is understood today, was imported from Europe in the mid-19th century. The first time the Muslim world learned of the word was 1848, when Maron Al Naqash from Lebanon translated Molière’s L’Avare (The Miser) into Arabic and performed it.

But there are some important theories rejecting this notion that theatre is something from the West.

Dr. Ali Aqla Arsan from Syria explains in his book Theatrical Phenomena among the Arabs that theatrical phenomena first appeared in ancient Egypt in the Pharaoh era (3100BC). He asserts that the ancient Egyptians had theatrical phenomena/acts because they had Gods for whom they danced and sang in a rhythmic way in groups. (Arsan 1978: 34; Arsan 1985: 30–31). He explores pilgrims’ ceremonies in pre-Islamic times. These were held twice a year, in summer and autumn respectively.

Also, the Iraqi historian Dr. Jawad Ali (1907–1987) writes about the pre-Islamic Arab culture that all the tribes gathered to celebrate even if they had different Gods. The Arab tribes had their own dance, music and rhythms. They sang and danced to show that they were happy and thanked in this way the Gods. They sacrificed to the Gods. They held such celebrations not only when they paid homage to the Gods, but also when they had important guests from another tribe. (Jawad Ali 1968: Part 5, 122). Today we define these ceremonies as theatrical acts.

Another important statement is from the Iraqi archaeologist and historian Dr. Fawzi Rashid (1936–2011). He argues that theatre has its origins in neither Egypt nor Athens but in Mesopotamia. In 1967, he together with some German archaeologists excavated from the Sumerian city of Uruk (4000–3100BC) remains of a stage, where he believes Inanna’s Decline to the Underworld[2] had been performed. He shows that there were several theatre buildings in ancient Babylon, which flourished from approximately 1800BC onward. Dr. Fawzi writes that the Greeks first took theatre from ancient Mesopotamia before developing it.

Uruk (Photo provided by author)

The Iraqi dramaturg Yousef Al Ani (1927–2016) states that the ancient Sumerians tried to understand religious ceremonies and rituals, which were further developed and used for the compilation of their largest and oldest mythology, Gilgamesh (2100BC). Ani writes that the area that is Iraq today has always had theatre. The only time theatre became inactive was 1880–1921 (Ani 2004). This is, in my opinion, due to the start of Western colonisation over the Middle East.

Following the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, there emerged Iraq as a new country, bordered and designed by the British for their own colonialist profit, especially after they had found oil in Kirkuk, one of the most multicultural cities with a majority of Kurds.

In the Middle East, World War I (1914–1918) resulted in the fall of the Ottoman Empire allied to Germany and Austria, and division of the Ottoman provinces in British and French interest.

The secret Sykes–Picot agreement of 1916 concluded that today’s Syria and Lebanon would be dominated by France, while Iraq was to be put under British control.

Unlike the French regime in the Syrian mandate territories which also paid attention to culture, British control in the new Iraq was limited to military and they did not try to interfere culturally. They did not in particular give priority to modernisation, democracy and societal reform.

Despite conservatism and British domination, after 1921 the government of Iraq made many new rules and laws. In 1922 the first law of Actors and Artists’ Associations was issued. According to the law, people could organise their cultural activities and work more systematically, especially those who formed groups for different purposes.

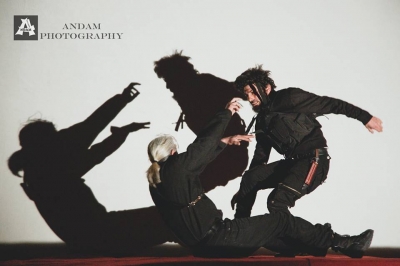

From long before this time, one of the most important and best-known theatrical forms of Islam is shadow theatre (Khayal al-Zil in Arabic), which is performed on a covered stage with a backlit window in the middle. The window is covered with white fabric and illuminated from inside. The actor plays with puppets made of different materials, such as leather, fabric or carton. The actor moves the puppets around between the light source and the window, so that the puppets’ shadows will appear on the outside of the window, such as on a screen, in front of the audience who have gathered to see the shadows and listen to the actor imitating voices of the characters in action.

Shadow Theatre from Kurdistan (Photo provided by author)

In Iraq, one of the goals of the Associations was to diminish the influence of shadow theatre, because the Associations considered it as low-level entertainment and they encouraged people to love acting. (Alzobidy 1967: 120). Shadow theatre had been very popular, often used to criticise different regimes and especially unwholesome trends in society. The new law set out to use theatre as a tool for social progress, to encourage people to go to school and educate themselves, especially the girls.

In the 1920s and 30s, theatre in Iraq became significant. In addition to performances for the people of Mosul and Baghdad, the English army staged 23 performances in English (Ibid). Starting from 1930, several plays were performed in English, French and Arabic; the topics were often societal, historical and nationalistic (being proud of their civilisation in the past). Iraq was essentially occupied by the British who actually decided everything, only they would put some Arabs on the surface to show that the country was run by its own people. There were always some Arabic public figures – puppets of the British – pretending to be power holders (as in China during Japanese Occupation). This drew widespread criticism in Iraq, both in Kurdistan and the rest of the country. Such political puppets became the target for protest, hate and shame during the nationalist movement at that time. Those plays in Arabic were performed in both dialects and the official language, because the official language (educated people can speak and understand it very well) is quite different from the dialects (that the majority spoke). Sometimes both languages were used together as a device to highlight class difference, such as having a headmaster speak official Arabic and a cleaner speak dialect. The plays also examined how women were seen in society. Women roles were played by men until the late 1940s in Baghdad (the capital of Iraq) and the 1960s in Kurdistan.[3] Of particular note is that these men were subject to sexual harassment by other men in society.

From the 1930s onward, the political situation in Iraq became more and more unstable. Iraq experienced a military coup in 1936, then another coup d’état in 1941. During that time, the British accused the rebels of being Nazi-friendly and after a short war, they exercised full military control over the country. Al-Gaylani, who led the rebels, fled to Berlin where he established an Iraqi exile government.

After 1945, Iraq became a member of the United Nations but remained under Western dominance. The regime was extremely British- and American-friendly. Government leaders still came from high society, most notably Nuri As-Said who had been Prime Minister for seven terms. Nevertheless, there was more momentum in community development than before, and oil revenues began to bring positive effects to the young state. Residents of Baghdad and other cities became richer, and gradually began to adopt a Western ‘Britishized and Americanized’ lifestyle, but the rural areas were still very traditional. Tension in society grew due to the emergence of a strong communist party.

Theatre groups which had relations with Western powers and criticised the regime were often labelled as communists.

During this period, theatre was also more developed: Women began to work as actors; women and children could come and see performances staged in public places, only that women and men had to sit separately; some theatre students were sent to Western countries to further their studies; many theatre groups came on the scene and performed actively.

[1] Today, Kurdistan, homeland of the Kurds, is divided among four countries: Iraq, Iran, Syria, and Turkey.

[2] The FIRST theatrical piece in the world ever written for performance.

[3] However, some sources suggest that there were women acting in Kurdistan in 1925 and 1926.

本網站內一切內容之版權均屬國際演藝評論家協會(香港分會)及原作者所有,未經本會及/或原作者書面同意,不得轉載。