“I hate the history in me,”states teenage protagonist Fanny vehemently in the early part of this ambitiously deconstructive psychodrama by Hoyingfung. Theatre Fanatico’s new production at the Cultural Centre Grand Theatre at the end of October and beginning of November for the Legends of China Festival is described as a “dreamscape”that conveys “the absurdity of human history”. The choice of the word “human”rather than “Chinese”is significant in this context. We need to bear in mind that in Hong Kong’s bilingual theatre scene there is a line of segregation between Chinese and English which is all too rarely crossed, except by a few inter-cultural groups. In pragmatic Hong Kong style Cantonese language drama productions are rarely subtitled in English and vice versa. The Seventh Drawer, however, had its premiere in Singapore in English, before being rendered into a variant version in Cantonese for the Hong Kong target audience. Thus the present writer had the unusual privilege for a gweilo of really understanding the text not just in broader visual terms in live performance, but in the linguistic specifics on the pages. That was of course before the rehearsal process began to transform the words on the page into a different kind of magical dreamscape, a more concrete one, than the play reader’s broad-ranging imagination can achieve.

Try imagining a cross between Alice in Wonderland with heavy Freudian spin and an ordinary Chinese family chronicle, if you can, and you begin to appreciate the audacity of what Hoyingfung and Fanatico have essayed in this stimulating and provocative piece of theatre. Ho admits to attempting something more verbally complex than previous Fanatico productions, but it is clear from a glimpse of the creative mesh of the verbal with the non-verbal in rehearsal, that the production will be the opposite of static speech-making on stage. In fact, the ensemble approach to theatre-making that serves many Hong Kong groups, Fanatico included, extremely well is very appropriate for a piece that skillfully combines surreal and absurd evocations of Chinese family history.

Fanny sits secluded in Grandpa’s closet, his refuge from the increasingly alien and incomprehensible middle class pretences of contemporary Hong Kong. She engages in a surreal interior monologue in which her own voice, inflected with teenage angst over her puberty sexual awakening and family embarrassment, is counterpointed by that of Grandpa recounting the story of his youth and manhood. Born, like his granddaughter, on the 4th May, but unlike Fanny at the dawn of modern China in 1911, Grandpa’s life epitomizes that of the ordinary Chinese Joe (to use the American vernacular.) There was a wonderful BBC documentary entitled People’s Centuryreviewing the 20th Century from the perspective of the ordinary person as opposed to that of the movers and shakers, whose names, for better or worse, have gone down in history. Grandpa’s retrospective of a life lived confusedly forward, but best understood backwards, his unashamed obedience to the dictates of his ego and his id, as well as to all of the pleasure principles going, put me in mind of this documentary’s affirmation of the little guy’s role in history-making, however meaningless and absurd as Ho suggests all that historiography may be.

Grandpa’s life runs in parallel to all the “great events”of Chinese history of the 20th Century, the May 4th Movement, the Long March, Liberation and the Cultural Revolution, just as his confessions run parallel to the outpourings of Fanny’s conscious and subconscious and obsession with her own body parts and fluids. Like a two-part opera aria their motifs weave inside and outside one another until the moment of unison, arrives. Grandpa, stricken by heart attack, is held tightly by the distraught Fanny, who continues to hurl imprecations at “the blood sucking ghosts”of history and tradition.

The drawers of the play’s title are stage symbols, connoting memory and hidden desires, unexpressed wishes and experiences. These drawers are represented by the ensemble, as is the family dog whose natural, instinctive behavior allies him to Fanny and Grandpa, thereby suggesting a triangular on-stage relationship. Fanny’s parents and the rest of the real world are peripheral, as in Alice in Wonderland, implied and referred to as authority figures over both Fanny and her grandfather. Sweeping actions by the ensemble with old-style brooms convey a traditional sense of respect for the ancestors and at the same time a sweeping clean of those traditions in order for a fresh start to be made, or as Ho himself puts it, “an exorcism of the hungry ghosts”. The uncomfortable ambivalence toward Chinese traditions and culture that many Hongkongers, and certainly many of the younger generations, seem to experience is aptly and memorably communicated in the play’s rapid-fire free association of verbal and visual images.

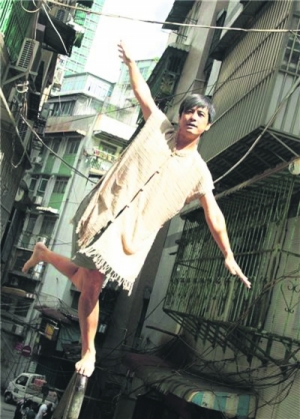

Fanatico’s multimedia production style will be complemented by live on-stage music to a score composed by Music Director John Chen. Ho’s projected background imagery, together with the added ingredients of words, music and physical acting will produce a kinetic, pictorial and linguistic feast for the theatergoer. The stage design - intended to give the effect of a bank of drawers in a herbalist’s shop –will offer the flexibility of an effective stage metaphor of the way the compartments of our memory and consciousness are triggered, often by random associations and stimuli, and also function somewhat like an illusionist’s cabinet, permitting the surrealistic and fluid version of the playwright to achieve physical embodiment in the theatre.

What comes across so powerfully to me –as someone who is familiar with Hoyingfung’s concerns in this play, and who remains (by the accident of being born in Britain rather than China) at a certain experiential distance from it - is The Seventh Drawer’s critical dissection of what he sees as the fetishism and neuroses of traditional Chinese family “values”.

The play represents a stinging indictment of that ingrained adherence to traditional views on sexuality and procreation, to the subordination of the individual to the collective and of all the other mantras which have stubbornly persisted despite the manifest destruction of that value system by the history of the 20th Century. At the same time the play celebrates a sense of humanity and family that goes beyond mere duty and endurance to encompass pleasure as opposed to shame, in the workings of the body. The family, like the body, is an organic entity, and thus the reconciliation of Fanny’s world and that of her dying Granpa is ultimately life-asserting.

Granpa’s list of rebellious acts in the play’s final epiphany –“the Seventh Drawer”–reveals the human connections that bind him and Fanny so closely. Both of them revolt with every fibre of their being against the deadening spirit of conformity to collective cultural norms. How fitting, then, that this play should be featured in the Festival. It encourages Hong Kong’s relatively young and hopefully critical theatre audience to cherish their personal history and culture on their own human terms. As we witnessed on July 1st and again in recent weeks, a mood of critical non-conformity to hierarchical arrogance is prevailing at present amongst the Hong Kong populace. In their own small way Fanny and her Granpa repudiate the notion that it is acceptable for the older generation to devour the younger, like Chronos in the Greek myth, or at least to sacrifice them to a perverted ideology. Let us reflect that in the global context 20th century history was memorably dubbed “the age of extremes”by historian Eric Hobsbawm, and that the madness of China was replicated throughout the century on a world-wide scale from Sarajevo (the outbreak of World War One in 1914) and back to Sarajevo (the vicious and bloody collapse of Yugoslavia in the 1990s). Like Fanny I hate some of the history in me –whether colonial imperialism or new-millennium imperialism, Bush and Blair style –but The Seventh Drawer reminds us that in asserting our right to our own personal histories we are so much more than pawns in hegemonic collective histories and cultures.

(原載於2003年10月《傳統再造》)

本網站內一切內容之版權均屬國際演藝評論家協會(香港分會)及原作者所有,未經本會及/或原作者書面同意,不得轉載。