2018年1月

Preamble

I am not a theatre critic; I rarely express views about shows I watch. I would only go as far as to describe a particular show as ‘not my cup of tea’ to my circle of friends. I also do not consider myself a drama critic, though I do have a fair share of knowledge on dramatic texts. Analyzing a range of texts were part and parcel of those days when I was still a theatre student. In case you are wondering, yes, I am attempting to disassociate myself from theatre and drama criticism.

So, why am I writing an essay about theatre critics?

Most of the time, I describe myself as a critic of theatre ecologies, or theatrologist. I take a special interest on the development of theatre in Singapore, Malaysia, Mainland China and Hong Kong, places where I have resided and/ or currently living in. When one talks about the theatre ecology, three groups of stakeholders come into the picture – artists, technicians, and administrators[i]. One can contribute artistically to a dramatic work as a playwright, director, and performing artist. Besides the artists, theatre productions need the inputs of technicians, who are the production and stage managers, production designers and technical managers. The third stakeholder in this ecology are the administrators, who are the policy-makers, fundraisers, marketers, managers and artists’ bridge to their audiences. These three groups of stakeholders are equally important in the upkeep of a healthy theatre ecology in any society[ii]. In fact, this is evident in the growing number of academic programmes, even at postgraduate levels, in technical theatre and arts administration, alongside arts practice programmes such as playwriting, directing and acting.

This is where my interest for theatre criticism comes in. I caught a recent staging of Waiting for Godot by Contemporary Legend Theatre (Taiwan) in Hong Kong[iii], and in one scene, the characters described theatre critics as the most lethal of weapons. This sarcasm towards critics is not unexpected. Some theatre critics are known to humiliate and write bitchily about theatre productions that they do not take a fancy to. Such an approach does not contribute to the field of theatre criticism, nor does it give critics a good standing[iv]. What roles do theatre critics play in the theatre ecology then? This essay attempts to shed some light on why theatre criticisms are necessary, and how critics can carry out their roles more effectively.

Roles of a Theatre Critic

In order to truly appreciate the roles of theatre critics, it is perhaps apt to first discuss the importance and necessity of the arts. Being a subject within the discipline of Humanities, the arts ultimately impact human beings and our cultures. On a personal level, the arts cultivate us to appreciate aesthetics and express our creativity. More importantly, the arts serve as a means of catharsis[v]. Tracing back to Enlightenment, (high) arts trigger deep thinking and reflections amongst the public, and in the process, enhance the intellect of individuals. On a societal level, the arts facilitate a critical dialogue between the society and its publics, by responding to and documenting important social and political events[vi]. Considering the importance of arts to the society and people, it should not come as a surprise that arts organizations are eligible to register as non-profit entities in many countries, which then allow them to receive public funding and tax-deductible private donations.

Given the impacts of the arts on humanities, theatre artists and technicians should strive to keep improving their craft so that the dramatic works they put together are not only just aesthetically pleasing, but also meaningful and impactful to the society. This is one area where theatre critics can play an important role. I am not suggesting that critics should assume this authority to ‘teach’ the artists and technicians what and how to improve. Rather, theatre critics should frame radical discourses on the dramatic works that engage artists and technicians (including audience members) to reflect upon and debate about[vii]. Criticisms should not depart from the context of the dramatic work in relation to its text and to the larger social construct where the play is staged. In a way, theatre critics should also be drama critics, who have good knowledge of the dramatic texts and aesthetics[viii].

The role of mediation between the artists/ art works and the audiences lies with arts administrators. If indeed the arts serve the society and its people, it makes perfect sense that arts administrators should ensure that the arts reach as many new audiences as possible, so that the benefits can be enjoyed by a wider population. Derrick Chong (2010) suggests that developing new audiences should be one of the key roles of arts administrators[ix]. Yet, to many people, art is still something quite distant, and is difficult to ‘understand’. In audience surveys conducted in Singapore and the United States, the lack of interest and understanding of the arts is a key deterrence to arts participation[x]. Some have suggested that theatre critics should, through their writings, help audience ‘understand’ the play. My disinclination of such a suggestion is based on one simple rationale - can anyone truly understand an artwork?

The main difference between arts and entertainment lies in their primary function, whereby the arts should really just be about what the artists want to say, whereas entertainment tend to focus primarily on generating content that trigger the audiences’ external stimuli[xi]. As such, to ‘understand’ art is actually quite irrelevant as no one can claim that they can fully comprehend what artists want to say for sure. Rather, the arts should be about what we eventually take away from the experience. This further stresses the critics’ role in generating discourses that engage the creators and the audiences. In a way, the process of discourse enhances the understanding of the works, probably in a more meaningful manner. To further boost audience’s understanding, theatre critics could also collaborate with theatre productions or festivals to offer dramaturgical researches and extended knowledge of the dramatic pieces for audience’s understanding prior to, or after experiencing the play.

Bourdieu’s Forms of Capital as a Framework

Currently, the barriers to entry into the field of theatre criticism is rather low. Anyone who is passionate about theatre and has a platform, online or offline, to share the reviews can become a critic. Do not get me wrong, I am not belittling the importance of having great passion for the art form. In fact, I think the love for drama should be the basic criterion for all theatre critics. Nevertheless, beyond this love for the art form, theatre critics should fulfill some other key criteria.

First, critics should have the necessary capabilities to frame discourses based on the contexts of the dramatic works, and in the process, facilitate and enhance the appreciation of these works. Next, while critics should avoid making snide remarks of works, they should never cave in to the pressures of offending artists and their organizations. In no circumstance should critics become a promotional voice for a particular theatre production. Last but not least, critics must consider their own sustainability and survival in the theatre ecology. After all, time and effort have been put into generating the criticisms. Critics should be adequately compensated for their contributions.

Having been a theatre practitioner for more than 15 years myself, I have come across many theatre critics. Those who are able to fulfill the criteria seem to have something in common – Capital. By capital, I am not merely referring it in the monetary sense, but in the wider definition of the term ‘Capital’ as synthesized by Pierre Bourdieu[xii]. According to Bourdieu, there are different interdependent capitals, such as Cultural, Social, Symbolic, and Economic capitals, that determine the social class of individuals. Bourdieu moves away from the reductionist view that only material goods and wealth, i.e. economic capital, affect one’s social standing.

Interdependency of the different forms of capital

(Image: Vickie Gunnells-Hodge[xiii])

Individuals with good education as well as a good taste for the arts, culture, and leisure are what Bourdieu describes as people with cultural capital. These individuals are likely to be influencers in their respective fields and disciplines. Another key determinant of one’s social class is social capital, referring to one’s stable and dependable network of peers. To Bourdieu, within this somewhat institutionalized network, individuals and groups are not only capable of sharing existing resources, but also developing new ones for their benefit. Finally, status, which is limited within specific cultural contexts and/or geographical locations, affects one’s social standing. Individuals who has built up good reputation are said to have symbolic capital. Taking Hong Kong as an example, an elected legislative council member is said to have symbolic capital, but this is limited within the city itself.

Education and Reputation – Cultural and Symbolic Capital

A theatre critic with strong cultural capital is one who has probably received relevant education in the field of theatre studies or dramaturgy. S/he should be equipped with good knowledge of theatre history and aesthetics, as well as the ability to dissect and evaluate a range of classical and contemporary dramatic texts. Currently, there are just a small handful of universities in Asia offering undergraduate and postgraduate programmes in theatre studies and dramaturgy. Based on my observation, Asian universities tend to focus on academic programmes for artists, technicians, and arts administrators. The large concentration of theoretical-based theatre studies and dramaturgy programmes are found mainly in the US, UK and European universities.

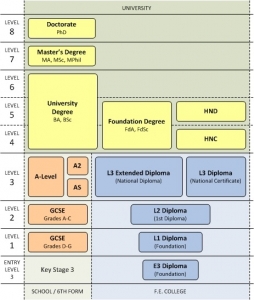

If going (back) to school is not an option, theatre critics can consider the external examination by London College of Music (LCM), which is part of University of West London (UK)[xiv]. LCM offers the FLCM by Thesis in Speech, Drama and Communication qualification[xv], which is based solely on a drama research project, and this includes research into dramaturgy or theatre studies. This process of research will certainly build up the critics’ capabilities on dramatic texts. Interested applicants are required to submit a short 500- to 1000-word research proposal for LCM’s approval. Thereafter, candidates can then embark on their research and eventually submit a 20,000-word thesis within a duration of two years. Candidates are expected to go through an oral examination after the thesis submission. Upon the successful completion of the thesis and the oral examination, candidates will be awarded the qualification. Currently placed at Level 7 with 225 credits on UK Ofqual’s Regulated Qualification Framework[xvi], this qualification is equivalent to a Master degree in the UK. One can pursue this qualification almost anywhere as there are LCM centres in different parts of the world, including Asia.

Qualifications and Credit Framework (QCF) in the UK

(Image: Accredited Qualifications[xvii])

Many established theatre critics are also academics in universities or arts journalists of well-known media. The reputation of the university/ media outlet plays a crucial role in the acquirement of symbolic capital, especially in the case for early career academics and young arts journalists. The dependency on the institutions to build up their individual symbolic capital is not without limitations. Many universities, such as the public universities in Singapore and Hong Kong, do not quite recognize arts criticisms as viable research outputs. Most of time, theatre reviews are published online or on printed media, and they do not quite ‘qualify’ as proper research with clear methodologies as compared to publications in top-tier journals. This discourages early career academics to contribute actively to theatre criticism. Young arts journalists face the competition of editorial space, which they have little control over. It is also difficult for them to depict their own style of writing, as their reviews could be heavily edited and shortened, which may dilute the discourses. On the other hand, senior academics, who are likely to be tenured professors and well-published, as well as senior arts journalists are more likely to have established strong personal reputation, and are less dependent on their institutions for symbolic capital.

Network and Survival – Social and Economic Capital

Watching a play and reviewing it seems to be a rather individualistic task. However, theatre critics should avoid operating alone, especially when their key function is to generate discourse and discussions on the dramatic works. It makes sense for theatre critics covering works in the same geographical region to form a network, and jointly research into the relationships between the works and the society.

The International Association of Theatre Critics (IATC)[xviii], which is formed under UNESCO statute in 1956, has put in place excellent networking opportunities for theatre critics all over the world. The association encourages the establishment of regional and national sections, bringing together theatre critics from similar localities to network and research into the particular region or country. There are also individual memberships for those who reside in countries without a section. IATC members are given preferred or free entry to many cultural institutions and events around the world. The association also takes on a key role in knowledge transfer, where they facilitate opportunities for theatre critics from different sections to share about the dramatic works from their respective region. IATC’s journal, Critical Stages[xix], has become a highly valuable resource to learn about the theatre ecologies and dramatic works of different countries.

Nigerian Theatre Critic, Professor Dandaura was invited by IATC Hong Kong to share about African theatre

(Photo credit: Centre for Cultural Studies, CUHK)

With the exception of full-time arts journalists, it is challenging for theatre critics to sustain a livelihood. Most of the time, theatre critics are writing reviews as a personal conviction and doing something else that probably pays the bill. Therefore, it is even more imperative for critics to work on their cultural and social capital, especially if they want to see themselves progressing as theatre critics. Many of my critics peers have adjunct teaching roles in universities and colleges or they have regular columns about theatre in newspapers and magazines. The Hong Kong section of IATC is a unique case, as it is the only IATC section that operates as a full-fledge organization with full-time theatre critics. In a good way, IATC Hong Kong has set the precedent for other sections to follow suit, and with adequate planning and lobbying (in collaboration with arts administrators), I believe more IATC sections around the world could eventually operate full-time.

In recent years, there seems to be a new opportunity for theatre critics. Many theatre festivals have set aside budget to invite theatre critics from the region to be attached to them for the entire run. The budget usually includes travel, accommodation, and some living expenses. Of course, critics would not receive such invitations without some level of cultural and social capital in the first place. On site, critics churn out reviews of the performances and publish them online. They also share their views of the performances in symposiums and forums that are organized in conjunction with the festival. Festivals see this collaboration with critics as a fulfillment of their education mission, so as to better engage their audiences. For the theatre critics, festivals become a valuable opportunity to build up additional social and economic capital. It is a win-win situation.

Arts Critic, Richard Chua[xx], in ACT Shanghai International Theatre Festival 2017

(Photo credit: Ophelia Huang)

Concluding Remarks

Writing is not the only medium to embark on a discourse of dramatic works. There is no hard and fast rule to dictate what media should theatre critics adhere to. It is absolutely possible to just talk about the shows, in the form of post-show talks or more formal settings such as forums and symposiums. In this digital age, it is also possible to review a performance via a live broadcast or a recorded version on video sharing portals. One major takeaway from this essay is that theatre critics should see themselves as active collaborators with theatre artists, technicians, and arts administrators. It should also be clear by now that each of the four capitals discussed in this essay are interdependent on one another. For instance, in order for critics to enhance their relevant education, they need the economic capital to pay for the fees. Along the same thread, one cannot achieve status and good reputation without a strong foundation of cultural and social capital. Theatre critics need to strategically plan and chart out their preferred paths. It is hoped that this piece of essay triggers some thinking and reflections amongst theatre critics as well as individuals who covet to become one.

[i] Bell, J. (2008). American Puppet Modernism - Essays on the Material World in Performance. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

[ii] Braun, K. (2000). Theater Directing : Art, Ethics, Creativity. New York: E. Mellen Press.

[iii] Website of the performance in Hong Kong: http://www.taiwanculture-hk.org/article/index.php?sn=1559

[iv] Clarke J. (2009). (Un)Critical Conditions. In Jordan E. (Ed.). Theatre Stuff: Critical Essays on Contemporary Irish Theatre. Dublin: Carysfort Press Book.

[v] Belfiore, E., and Bennett, O. (2008). The social impact of the arts. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

[vi] Kelly, M. (2000). The case of the 1993 Whitney Biennial. In Kemal, S., and Gaskell, I. (Eds.). Politics and Aesthetics in the Arts. Melbourne: Cambridge University Press.

[vii] Bennett, S. (1997). Theatre Audiences. New York: Routledge.

[viii] Crook, P. B. (2017). The Art and Practice of Directing for Theatre. Taylor & Francis.

[ix] Chong, D. (2010). Arts Management. New York: Routledge.

[x] Read the audience participation reports by National Arts Council, Singapore (https://www.nac.gov.sg/dam/jcr:9a606902-09d8-4505-b880-92e5da253de6) and National Endowment of the Arts, USA (https://www.arts.gov/sites/default/files/when-going-gets-tough-revised2.pdf).

[xi] Chartrand, H. (2000). Towards an American Arts Industry in Cherbo, J. M., & Wyszomirski, M. J. (Eds.). The public life of the arts in America. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press.

[xii] Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinction: A social critique of the judgement of taste. Cambridge, M.A.: Harvard University Press.

Bourdieu, P. (1986). Forms of Capital. In Richardson, J. G. (Ed.). Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education. New York: Greenwood Publishing Group.

[xiii] The image is taken from an article written by Vickie Gunnells-Hodge in 2013. Visit http://liahouston.org/2013/08/26/adding-equality-to-an-unequal-public-education-system/

[xiv] Visit LCM’s website at http://lcme.uwl.ac.uk/

[xv] Read up about the content of the examination here: http://lcme.uwl.ac.uk/media/1434/drama-and-communication-diplomas-sylabus-2017.pdf

[xvi] Visit the qualification information at Ofqual’s website: https://register.ofqual.gov.uk/Detail/Index/39214?category=qualifications

[xvii] Image taken from Accredited Qualifications. Visit http://www.accreditedqualifications.org.uk/qualifications-and-credit-framework-qcf.html

[xviii] Visit the website of IATC at http://aict-iatc.org/en/

[xix] Visit the website of Critical Stages at http://www.critical-stages.org/

[xx] Read the reviews by Richard Chua at http://richardchua.info/publication/

本網站內一切內容之版權均屬國際演藝評論家協會(香港分會)及原作者所有,未經本會及/或原作者書面同意,不得轉載。