2015年2月

Let me continue to talk about the most recent and unconventional theatre in Korea, which I mentioned very shortly in my previous essay. This unconventional theatre is embarrassingly minimal despite the great number and diversity of today’s Korean theatre productions. But among the young audiences, as I said before, it is increasingly welcomed anyway.

I have chaired the jury for the Dong-A Theatre Awards in Korea for more than ten years, until 2013. I quitted the job right after I was appointed the Artistic Director of the National Theatre Company of Korea due to conflict of interest, one of the most important principles of the code of practice of the IATC. Organized by a national daily newspaper, Dong-A Ilbo, this is the most coveted theatre prize in the country. We began to give a new prize in the frame of the Awards in 2003, to those artists making unconventional theatre—a Korean version of the Europe Theatre Prize’s “New Theatrical Realities” Award. Over the past ten years, however, we have only been able to determine six recipients, or a near-average of one every two years. As recent as in 2013, we had the 49th ceremony of the Awards, and again we could not give this “New Theatrical Realities” prize to anybody. This year, however, pansori singer and player Lee Zaram was awarded this rarely- awarded prize. This surely reflects the paucity of unconventional theatre in Korea with a slight possibility of change.

In Korea, the first avant-garde theatre movement began in the early sixties of the previous century. Under severe censorship by the then de facto military government, people developed a theatrical form called madang-geuk, a kind of guerrilla theatre based on the principles of the traditional mask dance drama. The mask dance drama has long sympathized with the struggling, abused common people and criticized the corruptive ruling class. It is a postmodern political theatre, performed in the form of site-specific theatre. The place and time for the show were communicated secretly, and the performers fled the site after each performance to avoid arrest by the police. Later, it was developed into a form of musical theatre by director Sohn Jin-Chaek who created the genre called madang-nori. Shifting the emphasis from politics to entertainment, madang-nori survived for almost thirty years by the time he publicly suspended the genre in 2007. At the request of the Korean National Theatre (not the National Theatre Company of Korea that I serve now), he revived the genre in 2014 very successfully with a modernized version of Korean classic pansori, Shimcheonjeon. The KNT will invite him every year to direct madang-nori hereafter, and I am very glad that this original Korean genre has been revived.

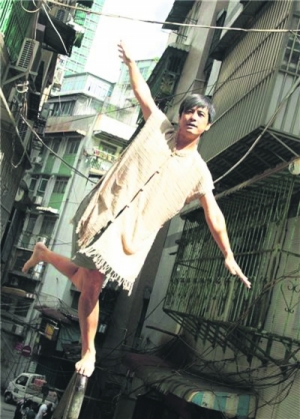

Along with this madang-geuk and madang-nori, another avant-garde theatre form was established in the form of intercultural theatre. People began to transform Western texts into Korean settings, contemporary or ancient, and employed aesthetic principles from the Korean traditional performing arts. This theatre hardly looks avant-garde from today’s perspective, but it was definitely so in the sixties. Now it has become one of the mainstreams of contemporary Korean theatre, represented best by four artists: Oh Tai-Seok whose adaptation of Shakespeare’s The Tempest in the setting of the 10th century Korea won many rave reviews from the British critics at the 2011 Edinburgh Festival; Yang Jeong-Woong who adapted Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream into a Korean folk play of goblins and won the grand prize at the 2003 Gdansk Shakespeare Festival; Lee Yun-Taek who put Hamlet in the frame of a Korean shamanic ritual and won the most enthusiastic responses from the Romanian critics at the 2008 Craiova International Shakespeare Festival; and Lee Zaram who wrote the music and performed in her own adaptations of Bertolt Brecht’s A Good Woman of Setzuan and Mother Courage and Her Children into Korean pansori—or one-person opera—performances, Sacheon-ga and Ukchuk-ga respectively. Both of the plays have been touring in Asia, Europe including France, and the Americas in 2012 and 2014, and recently in Cluj, Romania. Lee Zaram is the youngest and most internationally successful among the four I just named. She plays more than 15 characters in each show. She writes and masterfully sings her own pansori, a highly specialized form for which she has trained more than twenty years. Above all, she transforms the form of pansori from theatrical music into musical theatre.

Sacheon-ga

This practice of the Koreanization of Western texts is no longer considered avant-garde, or very new, or unconventional. It has become part of the mainstream. Recently, however, a new approach in this vein has been made by a young director named Kim Hyun-Tak, who frequently adapts classical Western texts but without “Koreanizing” them. His theatre has no obsession with the “Koreanness” that has long preoccupied his predecessors. Let me give you two recent examples. Medea on Media (2011), which Kim Hyun-Tak has adapted from Euripides’s play, was not approached psychologically at all. As the title implied, Kim put Medea in today’s culture dominated by the political power of the media. Medea was neither the usual character of a woman full of homicidal hysteria, nor a warrior of feminist fights. The play was not approached ideologically either. She was deconstructed both psychologically and ideologically. In Kim’s adaptation, Medea was not only a ruthless and sly perpetrator of blind violence who knew how to use the media to further her homicidal impulses, but she was also a victim of the media, which, as Patrice Pavis has said, “desperately needs crimes and pushes her to commit crimes” to satisfy a live TV audience thirsting for sensationalism and blood. Kim transformed the space in the basement of a local café into a typical studio where typical TV programmes were shot. The spectators were invited to become the TV audience. Scenes from the classical Medea were translated into the kinds of sensational and violent programmes we saw in today’s media. For example, Medea held a press conference to tell the Chorus her miserable situation brought on by Creon; in a scene from a silent movie, Medea pleaded with Creon to delay her exile by one day; on a live talk show, the exchange between Medea and Jason ended in physical violence; there was a scene of MMA (mixed martial art) between Medea and Glauce; violent computer games resembled those gun massacres seen on American TV news; one featured the lip sync singing of popular and pornographic songs—and so on. All of these scenes inspired by today’s media reveal the blind violence of our times, in which vulgarity functions as the equivalent of fate in Greek tragedy.

Medea on Media

Kim’s adaptation of Death of a Salesman (2010) was more minimalistic in both text and staging. Kim used the same basement of the local café, which you could hardly call a theater space, with its bare concrete walls and floor and without any theatrical lighting capability. Kim invited twenty people to his show of this modern classical tragedy. The show started with the last scene of Miller’s play where Willy committed suicide. This scene took the cinematic form of flashback and followed Willy’s long and difficult journey to a suicide imposed on him by the ruthless, capitalist ethic of success. Willy discovered an abandoned treadmill in the basement and got on it. From that time on, until the very end of the show, he ran on the machine, which refused to stop, or which he didn’t know how to stop, for a whole hour. Interestingly, Willy was played, not by a professional actor, but by a local resident, Lee Jin-Seong, whom the director picked up at a spa in the vicinity of his basement. Kim didn’t need a good professional actor, but a good real athlete who could run for 60 minutes on a fast treadmill. Indeed, Lee’s acting skills were so poor that during the recollections of his life on the machine, his lines were barely articulated and barely comprehensible, even for that limited number of spectators surrounding the machine. But it didn’t matter to Kim, who tried to deliver his—or Miller’s—message through Willy, who sweated on the treadmill, confronting the series of failures he had had at critical points in his life.

Death of a Salesman

Four years ago, the Dong-A Theatre Awards gave Kim the “New Theatrical Realities” prize in recognition of his “new” approach to theatre. He is certainly at the forefront of this “very new,” or “unconventional” theatre in Korea at the moment. I have already invited him to direct my company ensemble for Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet in his usually unconventional, experimental, physical style in 2016 when we will celebrate the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death.

Among the established dramatists, Park Keun-Hyeong is the most unconventional in his approach to realistic absurdism. His most recent success is Don’t Panic Too Much (2009), which is by far the best in terms of dramatic form and its thematic contemporaneity. With the situation and characters similar to those of Sam Shepard’s Buried Child, or Harold Pinter’s Homecoming, Park portrayed the absurd world. With Father as present absence, Mother as absent presence, an irresponsible first son, his wife flirting extra-maritally and in front of her brother-in-law, the second son suffering from constipation and missing Mother who had deserted the family, the composition of the family itself foregrounded the disintegration of the family. Park epitomized familial disintegration through the minutely detailed everydayness of the dramatic actions; he also transcended the limits of realism and moved toward absurdism or modified realism by employing highly expressive devices.

Choi Jin-a has recently joined this group with her 1-28, Cha-Sook’s House (2010), in which she lectured about house construction by way of her characters who were trying to build a new house on the site of their old house. No particular dramatic purpose was revealed. They just recollected their memories of the old house and their late father who built it, and tried to realize their concept of how a house should be designed. The dramatic action flowed from the discussion to the completion of the house’s construction. One common feature of these dramatists is that they write these everyday plays in order to highlight the absurdity of our daily lives, which have already become absurd enough.

Cha-Sook’s House

Director Ko Seon-Woong does not believe in the semantics of language, and takes it only as a kinetic element in a highly performativity-oriented play such as Killbeth, his parody of Shakespeare’s Macbeth. You can find one of the raves of the show in the 4th issue of the IATC WebJournal, Critical Stages (www.criticalstages.org). Ko has long been unconventional in his approach to theatre production, but very popular even to conventional theatre audiences. His deviation from conventional theatre has proved to be simple enough to be easily perceived and enjoyed even by unsophisticated spectators. He is playing the role of a bridge between unconventional and conventional theatre, by being both experimental and popular at the same time.

In this article, I have tried to name those theatre artists who are very likely to lead Korean theatre in the near future with their unconventional but easily perceived theatre. I have invited all of them to the National Theatre Company of Korea for ‘Unconventional Theatre Festival’ which will take place yearly from 2015, with shows scattered throughout the year. I hope this festival could create new and young audiences in Korea and bridge Korean theatre to world theatre. Thank you.

本網站內一切內容之版權均屬國際演藝評論家協會(香港分會)及原作者所有,未經本會及/或原作者書面同意,不得轉載。