|

2018年10月

Australian theatre presents conundrums on almost every level, geographically, historically and socially. With a landmass the size of continental North America, but a population equivalent to the city of Shanghai, the term “Australian” operates in a different way than the national labels of smaller, more densely developed countries. It would take a good walker two months to tramp from east coast to west, and up until 1917, when the state capital of Perth was finally connected to South Australia by rail, that was how part of the journey usually had to be completed.

The distances from Australia to overseas countries are almost as great. Captain Cook and the First Fleet – the eleven ships that claimed British colonial suzerainty over what is now Botany Bay in Sydney in 1789 – took three months to sail from Europe, and three years to complete the round trip. Even the first commercial flight, in 1935, took twelve days. Contemporary flying times are shorter, but are no bunny hop. Beijing: thirteen hours. Washington: nineteen hours. Hong Kong: eleven hours. The historian Geoffrey Blainey coined the term “the tyranny of distance” to encapsulate Australia’s unique physical and psychological spatiality: Not just a nation a long way away from the rest of the world, but a nation that feels it.

The factors of place and location are complicated by those of memory and time. White settlement of Australia is of recent origins, but the first nations peoples, Indigenous Australians, have been resident for 65,000 years at least (since before the last ice age). Over 250 different languages groups covered the country at the time of Cook’s arrival, and even today 120 are extant.

The culture of these communities is sophisticated and resilient: the Ngarrindjeri people of the Coorong; the Kaurna people of the Adelaide plains; the Wathaurong of the Bellarine Peninsula; the Gubbi Gubbi of the Sunshine Coast; the Whadjuk of Perth. In 1835, the year that Sir Richard Bourke declared Australia a terra nullis, he abolished the rights of some 750,000 people who were already living in it.

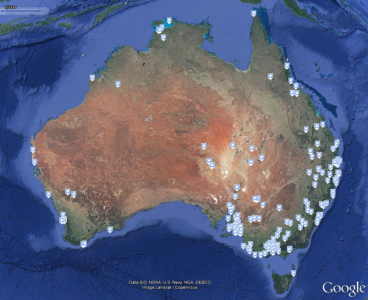

Google Earth: Distribution of corroborees performed for material gain, 1816-1904. Courtesy: AusStage database (www.ausstage.com.au).

These communities have performance traditions that make the earliest fragments of ancient Egyptian pageants seem recent by comparison. One of the first eyewitness accounts of an Indigenous “corroboree” was by Edmund Finn, who described a performance that occurred in 1836, just 14 months after British occupation of what is now Melbourne’s central business district: “The anniversary of the Regal Nativity [the birthday of King William IV] was 21 August, and on that day… after dark, the Aborigines had the good manners to treat the whites to a[n]… entertainment further away on the hill, where the Parliament Houses were opened just twenty years after. The blackfellows… for the first time performed before white men – their great national dance, known as the “ngargee”. Semi-circling a huge bonfire, they pirouetted… around the flames, which leaping up to the sky, illumined the then houseless surrounding country.”

The moral ambiguity and violence of white settlement was supplemented by successive waves of migration thereafter, making Australia one of the most heterogenous nations on earth. Multiculturalism is less civic aspiration than stark social fact, with half the population either born overseas or with one parent born overseas, one in five arriving in the last six years, and 300 different languages spoken at home. “Difference” is often invoked by intellectuals and politicians, in a tone of either praise or disparagement. In no other country is the term one of such general non-application, given that there is nothing to be different from. In Australia, “difference” is all that exists.

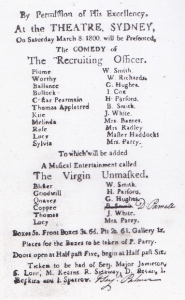

Playbill of the 1800 performance of The Recruiting Officer. Courtesy: Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales.

The first theatre performance by white settlers occurred on 4 June, 1879, a few months after the First Fleet landed. The Recruiting Officer, was performed by convicts in a mud-walled hut for the entertainment of around 60 dignitaries, among them Captain Arthur Phillips, the new British Governor. David Collins, Deputy-Judge Advocate of the colony noted that “the aims of this first company of players were modest. They professed no higher aim than humbly to excite a smile, and their efforts to please were not unattended with applause.” No record of the performance was passed on to London. Convicts were supposed to be doing more practical things than putting on plays.

It could be argued that a conflicted attitude towards artistic pursuits has plagued Australians ever since, what the critic A A Phillips in 1960 famously dubbed “the cultural cringe”. For all that, Australian theatre is numerically significant. The AusStage database, the online record for live performances in Australia, and by Australians overseas, contains over 100,000 separate performance events. It lists 9,500 venues, 14,500 cultural organisations, and 133,000 contributing artists. For a post-white settlement history of a little over 200 years, that is a significant record. Australian theatre certainly exists quantitatively. The main questions are qualitative. What kind of theatre is it? Indeed, given Australia’s geographical, historical and social complexity, what kind of theatre can it possibly be?

The critic Peter Holloway wrote in 1981 that “[a] not infrequent observation made of Australian drama is that it has proceeded by a series of fits and starts, of continual rebirths, like the phoenix from its own ashes. Each new generation of dramatists has had to regain its craft, its Australianness, and its confidence, from its own resources.”

Viewed artistically, it can be argued that Australian theatre has continued the nation’s tendency of historical erasure, as it has ticked through from Indigenous corroboree to Victorian melodrama, to Edwardian variety, to mid-twentieth century repertory, to late twentieth-century alternative drama, to post millennial/post dramatic, discarding each stage as it goes on to the next.

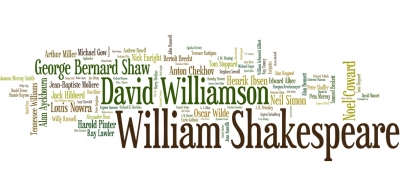

Word cloud showing popularity of playwrights performed in Australia. The larger the name, the most frequently produced. From the AusStage database, 2018.

The most popular Australian playwright, it comes as no surprise, died 173 years before the First Fleet set sail. Aside from regular productions of Shakespeare, it is hard to find evidence of meaningful continuity in the “history of beginnings”, that another critic, Peter Fitzpatrick, identifies as Australian theatre’s chief characteristic. This said, five historical periods of activity can be identified that have had an accumulative result, even if they don’t indicate the development of a national drama in the European sense (assuming that sense makes sense for Australia, another question altogether).

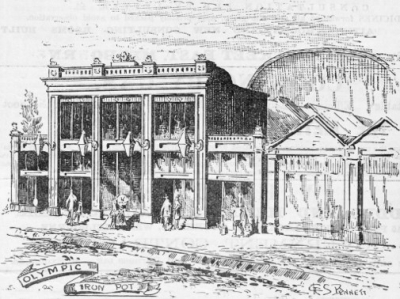

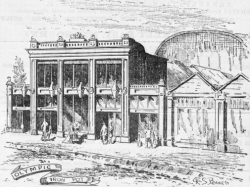

Exterior of the Olympic Theatre, Melbourne, circa, c 1855.

The first period runs from white settlement to 1870. In these ninety years, the first venues were built – like the Olympic Theatre in Melbourne (1855), nicknamed the Iron Pot for its notoriously high temperatures in summer – and the first Australian plays staged, mostly clones of British melodramas and touring minstrel shows, the latter particularly popular after the gold rush in the 1850s. The first, purpose-built mainland venue, the Theatre Royal in Sydney, was opened in 1838, and George Coppin, the “father of Australian theatre”, first appeared there, going on to woo audiences in Hobart, Melbourne and Adelaide in the following decades.

As a successful producer, Coppin’s tastes for sumptuous set designs were accused of providing “evidence that upholstery was going to triumph over acting”, but this didn’t deter now-wealthy colonists from enjoying all kinds of performances which it did not bother to categorise into “high art” and “popular entertainment”. This is another defining trait of Australian theatre, a positive one: that the difference between “legitimate” and “illegitimate” theatre, so significant in Britain and the US, meant little in a country where a small, dispersed and bored population was keen to experience whatever culture it could get its hands on.

J C Williamson, founder of "the Firm".

In 1874, the American actor and stage manager, J C Williamson, appeared in a play he had brought with him from California, the aptly-named Struck Oil!, a second period of development becomes evident. A comic performer of great skill, the success of this entertaining vehicle allowed him to build what, by the time of Williamson’s death in 1913, was the most extensive, wealthiest and complex theatre empire in history. It was co-extensive, of course, with the actual British Empire, and within its pink-inked territories, Williamson and his partners shunted actors from all over to perform for audiences in Australia, New Zealand and South Africa. Not even the terrible depression of the 1890s, which saw the country’s economy buckle under a collapse in property prices, stopped the growth of “the Firm”.

In the 1920s, the situation for live theatre was changed all over the world by introduction of “the talkies” – i.e. sound films. In this third period, the Firm reduced in operation, but retained a monopoly hold over every level of professional production in Australia. Its tastes had always been decidedly commercial, but by now this had begun to pall. Non-commercial theatre companies began to spring up, of which perhaps director Gregan McMahon’s Melbourne Repertory Theatre Company and Sydney Repertory Theatre Company, were the most influential. These and other “little” theatres around the country began to program Australian plays in numbers. In 1922, the Pioneer Players, the first company dedicated to Australian drama, was founded by playwrights Louis Esson and Hilda Bull. From this time until the 1960s, it was the “little” theatres in which the most genuinely Australian work was presented.

The fourth period of development is so distinct it stands out almost as a historical era unequivocally. Australian society slumbered through the 1960s. Despite its involvement in the Vietnam War, which was a matter of bitterly divided political debate, culturally it remained cautious, conservative and dull. This changed in November, 1972, when Gough Whitlam, the first Labor (i.e. progressive) Prime Minister for twenty-three years, came to power and changed the mood as well as the legislative reality of the country in a few short years. Government subsidy for culture doubled, and this had a marked effect on the performing arts. Companies like the Nimrod Theatre in Sydney and the Pram Factory in Melbourne were audacious in programming not just new Australian drama, but plays that were radically different in tone, style and audience impact. The so-called “New Wave” was probably the first time Australian playwrights got noticed overseas. In 1972, the playwright David Williamson – the largest name on the word cloud above after Shakespeare’s – won Britain’s prestigious George Devine Award. In 1976, his play Don’s Party was staged by the Royal Court Theatre. Since that time, playwrights like Andrew Bovell, Joanna Murray-Smith, Tom Holloway, Daniel Keene, and Patricia Cornelius have regularly received overseas productions.

The fifth and final period of activity is the hardest one to characterise, as it is the one going on now. It shows contradictory features – a continuation of the conundrums that mark Australian theatre – indeed of the nation – overall. On the one hand, some Australian theatre artists are now household names all over the world: the actors Cate Blanchett, Russell Crowe, Hugh Jackman, Hugo Weaving, and Toni Collete; the directors Simon Phillips, Simon Stone, Benedict Andrews, and Barry Kosky; the designers Brian Thomson, Kristian Fredrickson, Sue Blakemore, and Gabriela Tylesova.

These practitioners produce works of startling originality and quality. And yet, it has to be said, that Australian drama is not often its recipient, that their work is of “world standard” because it conforms to the standards the world sets. The phrases that might describe something closer to home and more innate – the Australian stage voice, or dramatic vision, or style, or styles, or stories – continue to define the second rung of professional work rather than the first. The exception is, of course, Indigenous theatre artists, who do not need to be susceptible to the blandishments of global culture because they already have one of their own.

本網站內一切內容之版權均屬國際演藝評論家協會(香港分會)及原作者所有,未經本會及/或原作者書面同意,不得轉載。