Documentation as Preservation

The performing arts are an ephemeral art form. This means that once a performance, workshop or session has finished, there's very often nothing tangible left over. If an audience member walks into your auditorium a day after a production has closed, what will they see? They will see blank walls, house lights and a dusty stage. The magic of the theatre will have evaporated. This is the opposite of the visual arts and literature, art forms which by their very nature produce a tangible output.

So, this is where documentation steps in—to me, the term “documentation” describes any kind of resources (of any format or media) that serves as a long-lasting record of your practice as a performing arts practitioner. Seen in this light, “documentation” covers a wide range of materials—from resources produced as a matter of course (like programmes, reviews and marketing materials) to those produced especially for the purpose of recording certain aspects of a project (such as video interviews with the production company, photo essays and workshop toolkits).

Documentation as Access

You could not consume a live performance if you were not in the right space at the right time. Only a certain (often very limited) number of people are going to see your theatre practice in person. However, that doesn’t mean we don’t want many more people to understand the importance and impact of our work. If you were not there, the only way you could get to know a performance would be through its documentation.

Truly, we are seeing a lot more digitised performance recordings around the world at the moment (especially due to COVID-19). However, we know that the performing arts is a live art form and so it is my belief that any recording of a live art form is a representation of that live art form and not a replacement—it cannot escape from being documentation and cannot pretend to replace the liveness of the theatre.

When I walk out of the theatre having seen a live performance, it is true that I—and all my fellow audience members—am left with memories of a production. Is this in itself a form of documentation? No—and for two simple reasons. It is neither enduring (which means the memory will last in the same form forever) or reproducible (which means I could copy and distribute the memory). Memories are certainly a great starting point for producing all sorts of formats of documentation, but it is not until you get it down on some sort of media (whether paper, online, images, videos, audios, etc.) that it can usefully be seen as documentation.

This is because, when we get back to basics, the act of documentation is about providing access to processes, activities, outcomes and impacts of the performing arts that otherwise would not have been externally visible to those who were not in the room at the time. Documentation is the record that anyone can look back on to reflect, learn and understand a performance that has already taken place.

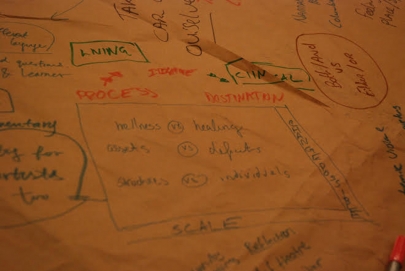

Feature image of Dialogue – The Community Performance Network

Documentation as Knowledge

I often describe documentation as being a “way of knowing” about a performance or project—a resource that, in the future, will be used as a tool by people to understand the original event. This is why documented resources are so important—they are the only enduring and reproducible means of constructing, producing, contributing, shaping, revealing, communicating and sharing knowledge about a performance or activity that no longer exists.

In our increasingly data-driven world, we know that knowledge is currency. The act of documenting captures knowledge and the resulting document itself is a tool that shares this knowledge around. And the great news is, to use a cryptocurrency metaphor, you can literally mine your own performing arts practice to create more and more of this type of currency.

Documentation as Power

If documentation is all about knowledge, and knowledge is currency, then it follows that documentation and power are very much connected. Let’s put this in a simpler way—documenters tend to have a lot of power. They are the ones who will create the official record of what happened. People will read, view or watch their accounts in the future with some respect for the authority that the documenter gives on the performing arts practice being described. They are, in effect, writing their own version of performing arts history.

It is important to remember that, even if it seems otherwise, documentation resources only represent the viewpoints of the documenters who create them. A performance might have been viewed by over 5,000 people, many of whom might have liked it, but only one critic may write the review that destroys its reputation. If you are reading an account of a theatre workshop, it is common to see comments such as, “Like all the other participants, I loved it and learned a lot.” Of course, this might be true for the majority of participants in the room, but we should not assume that one person speaks for everyone with complete accuracy.

This is why there are many important questions to consider about who is producing the documentation. Whose version of history is being written? This is especially important because documentation will not disappear in the same way that the theatre production will—it is enduring and reproducible and so has the power to leave a legacy.

Documentation as Storytelling

As theatre makers, we know that the best way of communicating something is by carefully constructing a story, and that the same story can be told in all sorts of different ways by different people.

Like all good stories, any type of documentation will focus on certain key elements that the storyteller wants to communicate. It does not describe the entirety of a production—if we wanted to recreate all aspects of a performance, we would need to restage the production completely. Instead, documentation tells one or maybe two stories of a production at a time which represents different aspects of a performing arts practice but does not replicate it.

One problem you are going to have is that you probably won't know at the time that you start documenting what is going to be most relevant by the time you get to the end of your activity. So, the narrative is certain to change. Similar to a theatre director embarking on rehearsals, you will most likely set out with a plan and an intention, but this will probably change and develop as time goes on. That is how creativity works, that is the nature of performing arts practice, and the nature of documentation initiatives. Dialogue – The Community Performance Network encourages the professionals that we work with to see all of their documentation resources as “live documents”—materials that can be changed, updated and modified, and not as materials “set in stone”.

Working at Dialogue

Nonetheless, documentation is—at a basic level—a story that the documenter wants to tell their audience. It is very much like producing a play or writing a novel. So, you need to decide who you want your audience to be—funders, other theatre artists, members of the public? You can have a beginning, a middle and an end. You need to decide who the characters are. How does the story progress? How does it move forward? What is the moral of the story? What is the thing that you want your reader or your viewer to come away with from that piece of documentation having learned about your performing arts practice?

Documentation as Subjective

These are all very subjective and creative questions, something that is perfect for theatre makers as we are used to being faced with these all the time.

It is important to think about who your storyteller is going to be. If we have three storytellers each telling their favourite story from a production, they will tell three completely different stories—and that is fine. It is important to recognise, and even celebrate, the subjective nature of any type of documentation.

Many will say, “Well, we are just using video recording equipment. We press record. We have a video. That video is fact. It’s not fiction.” This is not quite true as it is neither fact nor fiction. It is somewhere in the middle. “Fiction” would imply that it is completely creative and original, and a product of the imagination—and that is not true in the case of documentation (unless you are being very dishonest!). Documentation is always based on fact, but is always subject to creative and subjective decisions. We do not simply press “record” in any objective sense because, before we press the big red button, we will have already made subjective decisions about what we film, when we film, how we edit, and who the film is for. So, to take into account all of these creative decisions, no matter how “accurate” we try to make our documentation, we describe ourselves as constructing documentation.

Documentation as Presence and Absence

Just as there are many aspects of a performance or workshop activity that we choose to be present in our documentary accounts, there are also elements that we choose to exclude. Next time you see some documentation about a performing arts event, I challenge you to consider which aspects of this performance or activity have not been included in the documentation.

What would you like to transform?

It is a really interesting exercise because you suddenly realise that they probably have not mentioned the big disaster they had before the opening night, the fact that they learned to use a different ticketing strategy for next time, or that the director regretted casting a certain actor for a role.

Earlier in this article, I spoke about documenters having a lot of power. In a similar but different way, let’s consider why documentation tends to be produced in a privileged context. This does not necessarily mean financial privilege (but it often does). It means that those chosen to document performing arts work tend to be good writers, talented photographers, or celebrated video makers. They tend to be fluent in the language they are using for the documentation. They tend to know someone high up in the production company—either directly or through their contacts (otherwise, how else would they have gotten the job?). They tend to have some kind of professional background in the performing arts too. These are all admirable qualities, and there is no reason why documenters should be criticised for this. However, it gives us an interesting question to think about: In what ways, would the documentation tell a different story if someone without these advantages told their version of the story?

Documentation as Creative

It is also important to recognise that different storytellers will use different formats of storytelling. Like each theatre director having their own aesthetic, each documenter has their own approach to the work. Unfortunately, there is a historic perception that a documenter sits in the back of a room with a clipboard and ticks boxes. Seen in this light, the work of the documenter is boring, dry and dull—full of statistics and long reports. There is, of course, no reason why it has to be like this.

Just as theatre directors can challenge the status quo, so can documentation teams. At Dialogue, we believe in closely aligning the aesthetic of the performing arts practice being documented, with the style of documentation that we use. So, a creative, participatory and multimedia performance is best documented using a creative, participatory and multimedia documentation process.

Documentation as Evidencing Impact

Having navigated all of these very tricky practical and philosophical questions I have written about here, it is important not to feel too overwhelmed! Remember that there is no “perfect” documentation—just like when we tell a story, we cannot ever achieve 100% perfection (there will always be strengths and weaknesses in anybody’s documentation).

Ultimately, what most performing arts practitioners need is evidence that demonstrates, explains, proves and communicates the impact of their theatrical practice. Your documentation should be a narrative of the impact that you want to have, that you are having, that you have had.

I am being deliberately controversial when I use this word “impact”. It is sometimes criticised by artists and academics working in the arts as a word that makes them justify creating art, instead of just enjoying art for art’s sake. They complain that any talk of “impact” forces artists to comply with specified targets and outcomes so much that the original essence of the art is forgotten.

I will, however, reassure you that we can think about “impact” in much more productive ways than that. I challenge you to think about any theatre maker who created a performance without wanting to have any kind of impact on their audience. We all want some sort of impact, right?

The “impact” of a performance can include almost anything. Perhaps the most overlooked “impact” that professionals forget to describe in their documentation is, quite simply, fun. Imagine a performance made specifically for children, for example. You might want them to learn about history from the performance but I am sure you also want them to enjoy the experience. You want them to feel engaged, to be amazed by the stagecraft, and to go home having had a fun time. Seen in this way, “impact” does not have to represent a set of boring statistics or metrics given to you by an external third-party funder. It can (and should) mean different things to different performances and projects.

Documentation as Portfolio Evidence

Once you start collecting together a varied collection of documented resources, ultimately, what you will be left with is a body of evidence that can be used as a portfolio of the work that yourself (as an independent practitioner) or your company can show—like a collection of short stories that make up a larger book.

Any type of portfolio of evidence should be focused around demonstrating exactly what it is that your performing arts practice involves: what it does, what it sets out to do, what it achieves, and maybe even what it does not achieve. You also should be communicating about what is informing your practice. All of the inspiration. All of the different references that your practice is making upon other practitioners or other academics and how their work is informing your practice. And ultimately, it becomes a really good opportunity upon which to critically reflect on your practice.

Documentation as Forward-Facing

Fundamentally, I would encourage everybody to reject outdated understandings of documentation as being an “endpoint” to a production or project, as a means of simply reflecting on the past. Many professionals end up quickly writing up a last-minute report to fulfil the documentation requirements of their funder. However, as I hope this article has demonstrated, documentation should be so much more than that.

I am passionate about the fact that documentation initiatives should not be an “ending” but a “beginning”. If documentation has been completed in a thoughtful, creative and suitable manner, the completed resources have an enormous potential to play in the future—they can inform research and teaching; support publicity campaigns; boost advocacy initiatives; assuage the fears of funders; stimulate learning opportunities; encourage innovation; foster networking and collaboration; save unnecessary duplication of work; advance monitoring and evaluation initiatives; and offer ideas, inspiration, reference points and case studies of aesthetic quality and best practice.

In other words, completed documents should not be seen as an endpoint in their own right. Instead, we should see them as a tool that can be used to inspire, learn and effect other creative processes. That way, they are very much the foundation upon which we can build future theatre practice.

Photo courtesy of Dialogue – The Community Performance Network

Writer's bio: Chris Blois-Brooke is the Founder & Director of Dialogue – The Community Performance Network and an applied theatre practitioner with experience in international drama education, community theatre and theatre for development. Chris’ ongoing research interests centre around the documentation of performing arts practice. Recent projects he has completed include managing the multimedia documentation projects at international events/congresses and facilitating participatory documentation of community circus, dance, theatre, and storytelling practice internationally. He has taught theatre-in-education programmes at both primary and secondary school level in addition to facilitating theatre workshops for young people around the world. Chris is also a theatre director with various credits, including two critically acclaimed five-star productions at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe. He continues to teach at undergraduate and postgraduate level on topics around performing arts documentation and holds a Master of Arts with Distinction in Applied Theatre from The Royal Central School of Speech and Drama, as well as a First Class Bachelor of Arts (Hons) Degree in Social Sciences from Durham University.