2019年6月

This commentary is a collective reflection on a presentation at the Chinese University of Hong Kong in 2017 and at the University of Malaya for a conference organised by Persatuan Angkatan Seni Lakon Interaksi, Kuala Lumpur dan Selangor (ASLI)[1] in 2018, both about the sustainability and new readings of Chinese-language theatre in Malaysia. I highlighted nostalgia and emotional reliance, and rejection, resistance and subversion as characteristics of the culture of Chinese-language theatre in Malaysia during that time in 2017 and proposed Paul du Gay’s Circuit of Culture as a preliminary model to map existing 37 Chinese-language theatre companies in the peninsula in 2018. In my research on Chinese-language theatre in Malaysia for over 6 years through direct observation, informed by other historical researches, from secondary sources, Chinese-language theatre in Malaysia could be broadly classified as Chinese theatre from China before the Second World War; Malayan Chinese-language Theatre after the war; contemporary Chinese-language theatre in Malaysia with the establishment of the Malaysian Institute of Art in 1989.[2]

As Chinese theatre in Malaysia reaches its near 100th year of existence, discourse about nature and characteristics of “Malaysia Chinese Theatre” has just begun.[3] Sim (2019) had it situated that 1989, with the establishment of the Chinese drama department in the Malaysian Institute of Art, saw the transformation in identity (or more specifically, characteristics). Young Malaysians might not have adequate inkling and memory to appreciate ideologies that propelled Chinese theatre from the 40s into the 80s. In addition, after Malaysia’s independence in 1957, the dominance of Malay ultras in the country brought about tensions between them and the other races, especially the Chinese, who viewed themselves as a cultural minority in Malaysia.[4] In addition, the 1971 Cultural Policy drafted due to a deficit of trust between the ruling class and middle- and working-class Chinese set down aesthetical parameters for arts and cultural activities in Malaysia.[5] The socio-political environment’s impact on the development of Chinese theatre in Malaysia largely goes unnoticed. Demographics of Malaysian Chinese have also changed over the years. Younger Malaysian Chinese are educated in English as well as the national language Malaya (for those educated in national schools), and Chinese (for those educated in independent Chinese schools) at secondary levels. They continued their educational pursuit into public and private universities in Malaysia. As potential theatre audiences in Malaysia, a pertinent question: Do they appreciate Chinese theatre in its original aesthetical form or otherwise? Perhaps more generally, how do they view Chinese theatre as compared to theatres of other language mediums in Malaysia?

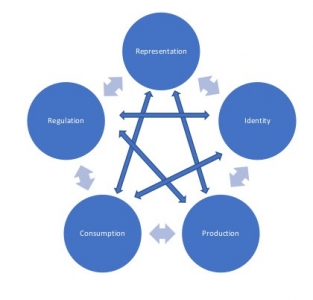

Furthering the existing discourse on nature and characteristics of Chinese theatre in Malaysia based on historical studies,[6] I find it productive to view existing Chinese theatre organisations in Malaysia through the lens of culture. Du Gay et al.’s (1976) Circuit of Culture provides guidance.[7] A new slate of contemporaneity in Malaysian Chinese theatre is formed within the community. In 2017, I pondered on the issue of sustainability of Chinese theatres in Malaysian’s pursuit of modernity. In my presentation at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, my contention was that nostalgia from emotional reliance, and natures of rejection, resistance and subversion are unsustainable as structures of feelings change, using Williams’ (1998) term.[8] Rather than to claim that socio-political changes complicate matters, perhaps it is new emergent theatre trends that make preserving identity a challenge for Chinese theatre in Malaysia.

From my observation from 2011 to 2017, new theatre companies, such as Anomalist Production and Theatrethreesixty, to name a few, have emerged, bringing world theatre, including Shakespeare and other modern plays, to audiences. New theatre in Malay language has also given a new voice to the staging of contemporary Malaysian aesthetics and sensibilities. Anomalist Production’s play Pohlithik revolving around the theme of political activism by Chinese students is a good case in point. The play told the story of a Chinese student’s aspiration to be the first Chinese prime minister in Malaysia and his leading students in a student election, which eventually ended in tragedy due to student riot ignited by racial provocations. A play about the plight of Malaysian Chinese in English and Malay, alongside vernacular Chinese language subverted Chinese theatre’s monolingual presentation of Chinese sentiments in Malaysia.[9]

Pohlithik by Anomalist Production (Photo courtesy of Nazrul Hazwan)

Meanwhile, Chinese-language productions by theatre companies such as MUKA SPACE and Pentas Project Theatre Production, approaching theatre (sic) (Malaysia and Taiwan), Kosong Space (NOW Theatre) and Pitapat Theatre (Sabah, East Malaysia), to name a few, have also created new vocabularies in Chinese-language theatre influenced by the practitioners’ trainings in Hong Kong, Taiwan and Singapore. They make innovations in form. Lastly, new independent theatre practitioners have also emerged engaging in smaller theatre projects that focus on socio-cultural and socio-political issues. One such theatre production is A Language of Their Own, by Singapore playwright Chay Yew, on LGBTQ+ issues and PLU, a Chinese theatre series produced independently by semi-professional theatre practitioner William Yap. Children theatre entitled Plastic City presented by Hong Jie Jie also broached on other less discussed topics, i.e. environment.

The Ring of the Nibelung by MUKA SPACE (Photo courtesy of MUKA SPACE)

Responding to Sim’s question at the end of his PhD research about the change of identity of Chinese theatre in Malaysia from Chinese spoken drama to Malaysian Chinese theatre,[10] I propose looking at the contemporary Chinese theatre companies through a cultural lens. Whether or not it is a form of identity change, it is a necessary move to understand how contemporary Chinese theatre in Malaysia react and respond to contemporary socio-political changes in Malaysia, not forgetting Chinese theatre produced, directed and performed by English-language Malaysian Chinese. Of all 37 theatre companies and collectives in Chinese-language theatre in Malaysia, how many of them would take a step out of the invisible language parameter to explore or make truly Malaysian theatre? A usual refrain in the theatre scene, which to a certain extent, chiding Chinese theatre in Malaysia for not fully embracing multiculturalism and diversity of Malaysian theatre.

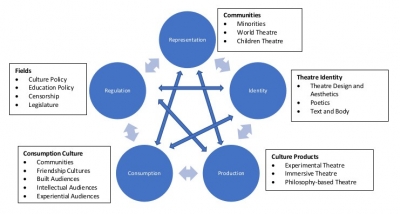

It is not easy for a Chinese theatre practitioner to embrace another culture through the adoption of a different language. A Chinese structure of feelings is built through a long period of cultural exposure. The context in which Chinese theatre is being produced needs to be understood and studied before any suggestion of crossing borders. Benny Lim and I outlined Malaysian theatre to du Gay et al.’s circuit of culture in a text collected by AICT-IATC journal Critical Stages.[11] Chinese theatre in Malaysia could also be studied along with the five broad categories of culture in the circuit. Sim’s PhD project has provided many valuable insights into the identity of Chinese theatre in Malaysia. While scholars are working on the representational aspect of Chinese theatre in Malaysia to society and country, I have yet to come across a contextual analysis of Chinese theatre in Malaysia, i.e. a delineation of parameters of any specific contexts.

Figure 1: Paul du Gay et al.’s Circuit of Culture

Walter Benjamin’s concern about art being devalued in the age of mechanical reproduction could be applied to Chinese-language theatre in Malaysia,[12] especially when existing theatre practices are being replicated by a new generation of theatre practitioners in an environment of limited historiography in Chinese-language theatre. Du Gay et al.’s Circuit of Culture could also provide a holistic view of the Chinese-language theatre in Malaysia in the context of Malaysia’s pursuit of a cultural economy while attempting to sort out existing challenges due to a change in the political regime.

Borrowing the Bourdieusian concept of Habitus[13] – habits and cultural practices that entrench within cultures – shifting paradigms in the habitus Chinese-language theatre community in Malaysia would take large efforts, both on the parts of practitioners and educators, key players in the community. Undoing the habitus (culture acquired by theatre practitioners from their seniors and teachers in schools) could allow for new experimentations and artistic practices.

In order to achieve this, looking beyond the Chinese language and culture is necessary. Du Gay et al.’s Circuit of Culture could be expanded to include the following sub-categories:

Figure 2: Sub-categories for analysis for Chinese-language Theatre in Malaysia

Building upon the legacy of Chinese-language theatre in Malaysia over the last 100 years, as the Chinese-language theatre in Malaysia progresses, new perspectives to the studying of the cultural phenomenon is necessary to further situate its role in Malaysian theatre, which in itself, a contentious area of study between the traditional and contemporary.

In the name to protect Chinese language and culture in Malaysia, linguicism inevitably permeates in the consciousness of the Chinese-educated in Malaysia. Having its roots in Chinese propaganda and activism in the early days of Chinese theatre practice in Malaysia, the spirit of activism for a form of Chinese-ness is alive in the contemporary Chinese theatre. I am not equating this form of Chinese-ness with Phillipson’s Linguistic Imperialism,[14] but one must be careful not to let it fester into a similar form. The use of Chinese language as an instrument to convey culture through literature needs further reflection in multicultural and multiethnic Malaysia as identities become varied due to English-language education, not to mention Malays who are adept with the Chinese languages. As race, language and culture practices continue to evolve and find their places in different periods of times in Malaysia (and Singapore), a cultural perspective to contestations would be a more objective platform for dialogue and intercultural experimentations. Chinese-language theatre in Malaysia could use the platform to initiate meaningful artistic and cultural exchanges.

[1] ASLI is an association of Chinese theatre practitioners in Malaysia. http://myasli.org/

[2] Sim, K.M. (2019). From “Chinese Spoken Drama” to “Malaysian Spoken Drama” – A Research on the Identity Shift in Malaysian Chinese Spoken Drama. Malaysia: The Heart Towards the Sun Theatre.

[3] According to Sim (2019), identity transformation of Chinese theatre in Malaysia began in 1945. Over 20 years, till 1965, Chinese-language theatre in Malaysia ceased to associate itself to the needs of pre-war period and adopted a renewed identity, marking a new contemporary at that time.

[4] Sanusi, Nur Azura, & Ghazali, Normi Azura. (2014). The Creation of Bangsa Malaysia: Towards Vision 2020 Challenges. Prosiding Persidangan Kebangsaan Ekonomi Malaysia,Vol. 9: 845-50; Goh, C. T. (1994). Malaysia: Beyond Communal Politics. Petaling Jaya, Malaysia: Pelanduk Publications.

[5] Bowie, N. “Fifty years on, fateful race riots still haunt Malaysia”, Asia Times, 29 May, 2019 [Online]. Available at: https://www.asiatimes.com/2019/05/article/fifty-years-on-fateful-race-riots-still-haunt-malaysia/.

[6] Chua, L. C. “5 things you don’t know about… the history of Chinese theatre in Malaysia”, ARTERI, 19 July, 2017 [Online]. Available at: https://www.arteri.com.my/2017/07/19/5-things-you-dont-know-about-the-history-of-chinese-theatre-in-malaysia/.

[7] Du Gay, P., Hall, S., Janes, L., Mckay, H., & Negus, K. (1976). Doing Cultural Studies: The Story of Sony Walkman. London: Sage Publications.

[8] Williams, R. (1998). The analysis of culture. In J. Storey (Ed.), Cultural Theory and Popular Culture: A Reader. Athens: University of Georgia Press.

[9] Chan, M. “‘Pohlithik’ empowers students to have a voice for others”, in Culture, Options, 23 April, 2019 [Online] Available at: http://www.optionstheedge.com/topic/culture/pohlithik-empowers-students-have-voice-others/. In this production, the use of vernacular Chinese makes a case for vernacular Chinese in theatres presented by theatres of other language streams, while the use of vernacular Chinese in Chinese theatre in Malaysia is still a topic of debate and discussion.

[10] Ibid. 2.

[11] Lim, B. and Chua, L.C. (2018). “Malaysia’s Theatre and its Circuit of Culture”, in S. Patsalidis, (Ed.), Critical Stages, Issue No 18 [Online]. Available at http://www.critical-stages.org/18/malaysias-theatre-and-its-circuit-of-culture/.

[12] Benjamin, W. (1968). The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. In H. Arendt (Ed.), Illuminations: Essays and Reflections (pp. 214-18). London: Fontana.

[13] Routledge. (2016). Habitus. In New Connections to Classical and Contemporary Perspectives: Social Theory Re-wired (2nd ed.) [Online]. Available at http://routledgesoc.com/category/profile-tags/habitus

[14] Phillipson, R. (1992). Linguistic Imperialism. New York: Oxford University Press.

本網站內一切內容之版權均屬國際演藝評論家協會(香港分會)及原作者所有,未經本會及/或原作者書面同意,不得轉載。