If one takes a look at the current performances of (alternative) Turkish theatre and also what happens within it, s/he can describe most of them as monologues, monodramas or solos. So my aim here is to explore why contemporary Turkish theatre frequently takes shelter in the monodrama or monologue form. Why are there so many singular narratives, especially female narratives? Why do young theatre directors and actors adapt the Turkish short stories, novels, poems written after the 1970? Moreover, why do they transform this sort of narrative into monologue or monodrama? It would be an oversimplification to answer these questions with the arguments of sociology, psychology, or the political condition of Turkey, such as because, ‘today individuals are becoming more and more lonely, ‘there is little possibility of dialogue both in social and political life’, ‘monologues and solo are easier to stage,’ ‘young artists are not given adequate financial backing by the culture minister.’ Even more justifications can be reproduced, provided that their validity is subject to scrutiny, but one major consequence is the theory the Turkish theatre began to reproduce: the stage (both physical and methodological) becomes more and more narrow, introverted and isolated in a traumatic way. Besides, it becomes clear that theatrical reality is undetachable from social, political changes than ever before. Is this narrowness a sign of closure and obstruction in the theatre, or is it a sign of opening up new possibilities in theatre studies of Turkey?

My suggestion is to view the situation of today’s Turkish monologue drama as both a reflection and a consequence of the country’s experience of modernization which is still underway. How does this experience affect the theatre and dramatic forms? In other words, does it dictate the dramatic forms in which we write, and how? We may also ask the question in a reversed way. Looking at the prevalent dramatic genre may give one some important clues about the changing aspects of social, political life. In this essay, I will roughly try to present an alternative reading of Turkish realist theatre by drawing a line from melodrama to monodrama in order to explain its emergence and development. Let me make it clear that the title ‘from melodrama to monodrama’ does not point to a linear, progressive reading of theatre history. Instead it refers to different dramatic forms – melodrama and monodrama – emerging and developing under the radical socio-political changes as a consequence of modernization. My argument is based on firstly, ‘melodramatic imagination’ prevailing in theatre studies from the later years of the Ottoman Empire to the new Turkish state – that is, the early period of the Turkish Republic; and secondly, the present-day monodrama can be read as a ‘post-melodrama’ which underlines the end of the melodramatic age. Here let me go into the first part of my argument.

The Melodramatic Age: From Tanzimat to the Republic

It is well known that playwriting appeared as a consequence of the Ottoman-Turkish modernization/westernization experience within the Tanzimat period (the state-sponsored political reforms of the mid-19th century which means restructuring). Within this period, Ottoman reformists and governors conceded the superiority of the West and started modernization to prevent the empire from falling. At the beginning, westernization started with taking Western technical innovations as a model or a prescription for reform in order to close the putative gap between the East and West. However, with the gap becoming larger than ever, the reformists decided to modernize every field. This led to irreparable consequences not only for political life, but for all the traditional representation forms from theatre to music to painting. All forms of representation changed because of the traumatic encounter with the Western world. Before this, theatre performance was almost improvised in an ‘open form’ not based on any written text. By this traumatic shift to Western styles, Ottoman intellectuals pointed out that theatre had to leave behind traditional forms such as Karagöz (shadow play), Ortaoyunu (theatre-in-the-round), and Meddah (storyteller), and turn itself from an ‘open form’ to a ‘closed dramatic form’ in accordance with Western theatrical conventions.

Namık Kemal, a leading intellectual and commanding political figure of the period, condemned traditional narrative forms for their lack of realist elements and began to write plays like Victor Hugo’s. This was a result of the ‘realism effect’ from the West, which particularly emphasized both rationality and romanticism. A palpable example of this shift was melodrama, the most popular dramatic form during the second half of the 19th century.[1] Namık Kemal and his follower Abdülhak Hamit Tarhan wrote so many love and historical melodramas which canonize virtues, goodness and patriotism. So this question arises: Why did these melodramas become popular for the audience? The highly polarized universe in melodrama where good and evil can be selected easily and good always wins, as Peter Brooks put it, was a product of the French Revolution.[2] Likewise, it fulfilled the Ottoman Empire’s political requirements to prevent its disintegration or collapse and to keep the people in unity. Besides, melodramatic rhetoric reflected people’s desire for democracy.[3] Thus, it can be said that melodrama is a subversive genre; it is conservative at the same time, because its dualistic and polarized discourse based on good and evil does not offer the audience any alternatives or possibilities. In a melodramatic universe, we the audience are always confined between two extremes.

A photo of Ottoman intellectuals and writers

However, what I would like to underline is that the melodramatic form kept going during the Republican period after the fall of the Empire, despite the Republicans’ denial of the Ottoman heritage and their intention to kill its past. From Tanzimat to the mid-20th century, melodrama remained dominant because of the ideology of Republican reformists. From the Ottoman Empire to the Republic, Turkish intellectuals and reformists set out to create a realist theatre in order to turn their gaze from dogma to rationality. In this case, theatre was used as a device to educate the common folks and to reinforce the Republic’s principles and reforms. Thus, this kind of modernization determined what would be included and excluded. The New Turkish state is thought to belong to the people who identify themselves as Turks, who protect the new state’s ideology. Everything out of this ideological stance, therefore, should be repressed and excluded. It is also in line with Kevin Robins and Asu Aksoy’s notion of ‘deep nation’, which refers to the nationalist and rationalist ideology of the Turkish Republic founded in 1923.[4] The main goal of the new state regime is to ‘reach the contemporary level of civilization’, which can be seen as the process of building a modern nation-state in its fullest form. Its new constituents are rationality, nationality, positivism, organic vision of society and a republican model of citizenship.

To this end, theatre, also ‘a sign of civilization’, had an important role in imposing these constituents on the people, which would in turn reinforce the Republican ideas. In response to such requirements, Republican intellectuals took the French theatre and Western realism as a model to construct a Turkish realist theatre. However, what this theatre produced – or what was produced within it (1923–38) – was not the same as that of Western dramatic realism. Turkish theatre scholar Beliz Güçbilmez, for example, asserts that while a story of the past is a constitutive element of the Western dramatic model from Sophocles’ Oedipus the King to Ibsen’s realist dramas, Turkish realist drama in the Republican era had no such stories that would build the plot. For Güçbilmez, the past-less of the Turkish realist theatre was caused by the discontinuity of cultural memory which was later reinstated by the Republican cultural ideology.[5]

Early Turkish realist theatre created a kind of utopic and idealized universe in which a character appears with his responsibilities to the state and society. He cannot appear as an individual who confronts society or experiences inner conflicts. He is shown as an acceptable citizen who struggles against the enemy and their ideas. This is why, for a long time, melodramatic and romantic elements persisted under the guise of a realist theatre in order to obey rationalist and nationalist ideology of the Republic. And this also brought about ‘a theory of lack’ (‘Turkish theatre has no characters but a lack of interiority in terms of Western theatre’).[6] For a national theatre aspiring to become a realist theatre, this is the cause of contradictions. As a realist theatre whose aim is to show and reveal the reality of life, Turkish realistic theatre had seemingly refused and had been too repressed to show its own reality – for example, the poverty of the people, narrow circumstances – and its own past from Ottoman heritage, creating instead an idealized, imagined reality both in social and theatrical life. As a consequence, anything incompatible with the new state’s ideology was marginalized and repressed, such as Kurdish question, homosexuality, transgenderism, feminism, etc, and this is still going on in Turkey today.

For these reasons, we may describe the Turkish realist theatre from the Tanzimat period to the 1950s as something between melodrama and putative rationality in bold outline, and may call this period the ‘melodramatic age’. Here, with melodrama, I mainly refer to the role of a national ideology in theatre and its imagined community. We can also say that it has an idealized and polarized dramatic universe. In other words, the equivalent of what Aksoy and Robins called ‘deep nation’ in Turkish theatre is the ‘deep melodrama’.

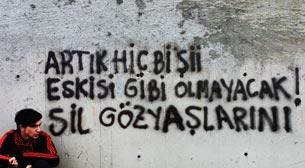

It never gonna be the same, wipe your tears: Monodrama as a Post-melodrama

During this period Turkish realist theatre was not comprised of melodramatic, nationalist plays. There were also antithetical examples, but they didn’t lead to a common dramatic style. Turkish theatre, however, has changed rapidly and radically since then. This melodramatic stance, thus, mostly disappeared in the so-called multi-party period which provides relatively liberalism.

Between the 1960s and 2000, Turkish theatre had experienced so many different theatrical and writing styles – from Brechtian epic theatre, vaudeville, political satire to absurd theatre, in-year-face theatre. But it was never the voice of the repressed and the oppressed, and never became as much a meeting point of the ‘others’ as now. It is no coincidence that this change happened after Occupy Gezi or Gezi Park Protests in 2013, when all the ‘others’ gathered at Istanbul and spread to other cities. These all-pervasive protests in every city of Turkey were not only against Turkey’s current ruling party AKP, but also the whole ideological stance of the Turkish Republic which rejects and represses differences, alterity, and otherness. The famous graffiti and slogan during Occupy Gezi – ‘Down with some things (kahrolsun bazı şeyler)’ – also summarizes the heterogeneity (because of the underlying ambiguity of the word some things [bazı şeyler]) of the ‘Gezi Community’ and its expectations.[7]

A symbolic representation of Occupy Gezi (June 2013), painted in miniature form

During Occupy Gezi, each occupant and protestor was both very different from and very similar to each other. They were the Kurds, homosexuals, transgenders, football fans, followers of Kemalist ideology, republicans, socialist Muslims, communists, radical leftists, anarchists, environmentalists, and artists. In short, they were those who, we think, never get together at the same place. Henceforth, it was a ‘community of those who have nothing in common,’ to borrow a phrase of Alphonso Lingis, or Agamben’s ‘coming to community’, or Jean-Luc Nancy’s ‘inoperative community’, instead of an ‘imagined community’ in terms of Benedict Anderson’s description, or ‘organic vision of community’ that I tried to discuss at the beginning of this essay as the model of official ideology of the Turkish Republic, and thus that of the modernization experience.

The major change in present-day Turkish theatre is, thus, the return of the narrative to monologue and monodrama, especially after the Gezi Park Protests. It should be noted that this model shifting is more apparent in the performances of alternative theatres that consist of the younger generation, rather than mainstream theatre such as National Theatre of Turkey. However, this change does not only mean that Turkish traditional narrative form turns back to a new ‘storytelling form’, but that all the subalterns who have been repressed, silenced and refused under the everlasting ideological period are now coming back with their own stories on a narrow, dark, ‘empty’ stage. Ironically, they adopt the traditional narrative form which is also rejected and neglected like themselves under the pressure of national and rational ideology. This inescapable choice also signals a new theatrical language in search of resistance or a counter-discourse against the official ideology. Now we the audience witness stories of women abused by men or a masculine society, of individuals who challenge the nationalist ideology in order to protect their own language Kurdish, of young homosexuals, transgender people who are looked down upon by the elites. My intention here is not only to present Occupy Gezi as a justification for today’s Turkish monologue drama, but to draw attention to the changing relationships between private and public spaces, the individual and the state after the protests, and to point out why new Turkish theatre is so eager to tell.

Theatre put idealized characters together as a reflection of the new republic’s expectations of art and culture in the first half of the 20th century. To this end, they were marked by a rationalist and realist touch. But because of the nationalist ideology and the need to frame it, they were only able to create a monochrome realist-national theatre between melodrama and rationality. Now, on the contrary, it seems that Turkish theatre is more realistic than ever, because it delves into the deeper reality of society, transforms the idealized character’s story into that of a subaltern, indeed on the stage which we also call ‘alternative theatre’. Hereafter, the stage is not an imaginary space for false cultural homogeneity and unity, but a meeting point of differences, a place for the repressed and the denied. If we rethink Turkish realist theatre whose plot has no past story, as quoted from Güçbilmez above, it can be said that new monologue dramas recall the past and all the things repressed within it. So, the return is not only the narrative form but the past as such, because the form of monodrama and monologue is mostly based on the (past) narrative. In monologue drama or monodrama, the character perpetually remembers, confesses his past experience. Theatre scholar Marvin Carlson, for example, calls the theatre as a ‘memory machine’ which re-tells, re-writes, re-acts.[8] Seen from this perspective, the monologue or monodrama can well be described as a ‘double’ memory machine.

Poster of theatrical production It never gonna be the same, wipe your tears, performed by Ahmet Melih Yılmaz and staged by Mek’an Sahne in 2014

New theatre says ‘it never gonna be the same, wipe your tears,’ to borrow the title of the popular monodrama written by Şâmil Yılmaz after Occupy Gezi which tells Gezi’s story through the eyes of a street child. In addition, new playwrights and groups, for example Yılmaz and his theatre Mek’an Sahne, say that everything we see and experience on the streets will be on the stage, that there will be no gap between the two. This is why we the audience see in his monodramas street performances with arabesque rap music, a character smoking weed, cursing, speaking the street language. It is significant then, that many of the current monodramas, monologue dramas, and solo performances have their voices and in this way, they still try to overcome the logic of the national ideology and its melodramatic imagination as the main consequence of this modernity experience.

Lastly, let me make a connection between melodrama and monodrama in the case of Ottoman-Turkish modernization. In the Tanzimat era, for the Ottomans, melodrama was the form reflecting people’s desire for social and political changes based on the constitutional monarchy. It was the renewal required by society, a proper genre to be the voice of the oppressed and the muted. But at the same time, it projected a highly polarized dramatic universe between good and evil, virtue and tyranny. The melodramatic form, therefore, serves two roles. On one hand it represents the desires, intentions, fears, hopes of the people, especially of the subalterns; on the other hand, as long as nationalism rises, it is hand in hand with nationality. It is the apparent dilemma of the melodrama.

This polarized discourse also brings to mind the current political debates in Turkey caused by authoritarianism. For a while it has been discussed that we Turkish people are divided into two sharp poles both in terms of political and cultural life, namely the Republicans and the conservatives. It can be said that our social and political lives have turned into a sort of melodramatic universe. Even under such political conditions, the government still wants theatres to stage more nationalistic plays again. It is important to understand that the Gezi community was not founded on this polarized discourse. And today, for the post-Gezi community, it seems monodrama is a proper genre to be the voice of the oppressed and the repressed – the so-called ‘others’ – in spite of making theatre more introverted than ever. If I go back to the questions at the beginning, it is obvious why the younger generation adapt some Turkish short stories, novels and poems written after the 1970s, which are based on deconstruction of the logic of the prevailing polarized and idealized discourse that I have tried to discuss throughout this essay. The stage of monodrama exposes what is approved and what is rejected in socio-political life. From melodrama to monodrama, the theatrical reproduction has begun to change on stage and to create a new relationship between theatre and reality. In this respect, the monodrama opens up a new possibility in Turkish theatre studies. But on the other side, its ‘mono’ dimension signals a closure. Is the stage becoming more and more narrow, introverted because of the audience’s encounter with character’s traumatic story?

Works Cited:

Aksoy, Asu and Robins, Kevin, ‘Deep Nation: The National Question and Turkish Cinema Culture’, Hjort, Mette and MacKenzie, Scott (Eds), Cinema and Nation, London and New York: Routledge, 2002.

Brooks, Peter, Melodramatic Imagination: Balzac, Henry James, and the Mode of Excess, Yale University Press, 1995.

Carlson, Marvin, The Haunted Stage. The Theatre as Memory Machine, University of Michigan Press, 2001.

Dağtaş, Mahiye Seçil, ‘Down with Some Things! The Politics of Humour and Humour as Politics in Turkey’s Gezi Protests’, Etnofoor, Volume 28, No 1, Humour (2016), pp. 11–34.

Güçbilmez, Beliz, Zaman/Zemin Zuhur: Gerçekçi Türk Tiyatrosunda Minyatür Kurgusu [Time, Ground, and Appearance: The Form of Miniature in Turkish Realist Theatre], Dost Kitabevi Yayınları, 2016.

Gürbilek, Nurdan. ‘Dandies and Originals: Authenticity, Belatedness, and the Turkish Novel’, The South Atlantic Quarterly, Volume 102, No 2/3, Spring/Summer 2003, pp. 599–628.

Uslu, Mehmet Fatih, Çatışma ve Müzakare. Osmanlı’da Türkçe ve Ermenice Dramatik Edebiyat, İletişim Yayınları, 2014.

作者簡介:Eylem Ejder is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Theatre at Ankara University, Turkey. She is a member of International Association of Theatre Critics (Turkey), and a member of the editorial board for IATC (Turkey)’s magazine Oyun (Play). Her writings have been published in European Stages, Arab Stages, Critical-Stages, Oyun. She studies theatricality, contemporary Turkish theatre, Ibsen’s dramas, and modern dramatic theory. She has been studying as a guest researcher at the Centre for Ibsen Studies, University of Oslo since June 2017. Her Ph.D. study is being supported by The Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey (TUBITAK) under the National Ph.D. Fellowship Programme.

照片由作者提供

[1] Here I mainly take the example of melodrama as an experience of modernization. But it does not mean the only genre was melodrama, or traditional theatrical forms had all disappeared. My aim is to trace the emergence and development of Turkish realist theatre. Other genres, like comedies, are thus excluded from my discussion. In addition, I focus on the model shifting from an ‘open form’ to the ‘closed dramatic form’ as a manifestation of the nature of this experience. And I think it can also be used as a metaphor for the ‘closeness’ of this modernity itself by dismissing the ‘others’ while opening itself to the West.

[2] Peter Brooks, Melodramatic Imagination: Balzac, Henry James, Melodrama, and the Mode of Excess, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995.

[3] For more, see Mehmet Fatih Uslu, Çatışma ve Müzakere. Osmanlı’da Türkçe ve Ermenice Dramatik Edebiyat, İstanbul: İletişim Yayınları, 2014.

[4] Kevin Robins and Asu Aksoy, ‘Deep Nation: The National Question and Turkish Cinema Culture’, in Mette Hjort and Scott MacKenzie (Eds), Cinema and Nation, London and New York: Routledge, 2002.

[5] Beliz Güçbilmez, Zaman/Zemin Zuhur: Gerçekçi Türk Tiyatrosunda Minyatür Kurgusu [Time, Ground, and Appearance: The Form of Miniature in Turkish Realist Theatre]. Ankara: Dost Kitabevi Yayınları, 2016.

[6] For a detailed discussion about this concern, see Nurdan Gürbilek, ‘Dandies and Originals: Authenticity, Belatedness, and the Turkish Novel’, The South Atlantic Quarterly, Volume 102, Number 2/3, Spring/Summer 2003, pp. 599–628.

[7] The word some things (bazı şeyler) has an uncertain meaning. It is not certain what some (bazı) is referring to. It is used as a device of rejection and criticism without any specific target. For more, see for example Mahiye Seçil Dağtaş, ‘Down with Some Things! The Politics of Humour and Humour as Politics in Turkey’s Gezi Protests’, Etnofoor, Volume 28, No 1, Humour (2016), pp. 11–34.

[8] Marvin Carlson, The Haunted Stage:The Theatre as Memory Machine. (University of Michigan Press, 2001).